A. Igoni Barrett's "Blackass" And The Afropolitan Debate

"Blackass" is a Nigerian novel about the Afropolitan fantasy and the painful reality of race.

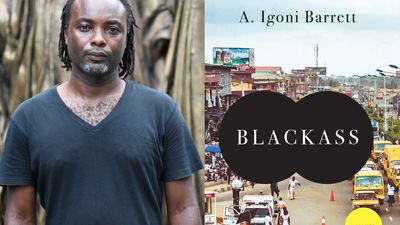

A. Igoni Barrett, author of Blackass. Photo courtesy of Victor Ehikhamenor.

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie once claimed in an interview that she only became aware of race when she arrived in America: “I really hadn’t thought of myself as black in Nigeria,” she said. “Identity in Nigeria was ethnic, religious…but race just wasn’t present.”

Of course, “race” is anything but black and white. Some black Americans might scan as “white” in Nigeria, while white people in Africa are sometimes horrified to find themselves to be a “minority.” And as Adichie’s third novel, Americanah, explores, Africans in the United States do not always see themselves (or are seen) as “black” (or at least not the same kind of black as American black people). Indeed, Americanah is a novel about Adichie’s own discovery and acceptance of her blackness: as Adichie did, her protagonist becomes a writer in America and writes her way through this experience. Like Adichie, she eventually returns to Nigeria after her writing (a blog called “Raceteenth or Various Observations about American Blacks (Those Formerly Known as Negroes) by a Non-American Black”) has given her the professional and psychological security that she needs to bring the novel’s romance plot to its conclusion.

In Americanah, then, there is a relationship between becoming black and becoming a writer. A racist world might reduce her to the color of their skin, but race becomes something she can affirm (instead of simply endure) when she makes it comprehensible, speakable. If her blackness begins with being observed, passively, Ifemelu’s “observations” put race in the active voice. By observing, herself, she becomes the subject of her own story. In this way, tragedy becomes comedy. After all, race is tangible and real, but it’s also absurd and incoherent. And while being misunderstood is a real experience, it’s not one that you can understand. It’s too viciously absurd. But if you can laugh at it, at least, you can live with it.

This is also why Ifemelu starts a blog: Blogs are not serious writing, nor expect to be taken seriously. Blogs are fragmented, spontaneous, and cheap. But they are also creative in the way that all autobiography is essentially fiction: social media allows us to create a self that we can only dream into reality. And just as Ifemelu turned to a cheap and popular mode of self-writing to make her experience livable, Americanah was Adichie’s foray into popular “genre”-writing, a novel that took its form from social media, a romance genre-fiction hybrid that can’t—like a blog—is too long, too personal, and too self-indulgent. It can’t be bothered to be edited, high-brow, tragic, or focused. It’s only interested in how to laugh, and thus, how to live.

*

On the surface, A. Igoni Barrett’s Blackass is like a photo-negative of Adichie’s Americanah. If Adichie’s Ifemelu learns to be black in America, Barrett’s Furo Wariboko wakes up to discover that he has become white in Nigeria. As in Kafka’s The Metamorphosis—a clear influence—Wariboko is transformed into a monstrous vermin: an oyibo, a white man in Lagos.

What does it mean to be white in Nigeria? If Adichie/Ifemelu discovered “race” in America, it was because of this country’s toxic presumption of normative whiteness; as Zora Neal Hurston once put it, “I feel most colored when I am thrown against a sharp white background.” Barrett’s protagonist, by contrast, learns to be white in Nigeria, a place where white people are so rare as to be spectacles, objects of curiosity. And if Americanah is an “Afropolitan” narrative, then the one thing Blackass isn’t, is Afropolitan. If Adichie was interested in how to be a black writer, I would suggest that Barrett is, first and foremost, interested in how to be a reader.

Like Barrett’s previous book—the short story collection Love is Power, or Something Like That—Blackass is an almost overwhelmingly Lagosian novel, drenched with untranslated speech and local references (so much so that Chinelo Okparanta compared it to a travelogue). Lagos is a city that needs readers, a massive and dense text that defies comprehension; if nothing else, Blackass is about the city that suddenly becomes visible once Wariboko is thrown clear from the life he had previously lived. As a white man, he sees Lagos in a profoundly different way. But the novel is also about the predicament of blackness in Africa, about the experience of race that Adichie recalled never having felt in Nigeria. It might not be easy to feel color against a black background—as we might reverse-engineer Hurston’s statement to read—but race is a global phenomenon, as global as empire and white supremacy.

As it turns out, being white in Nigeria means something; it means oyibo. It means that acquaintances shun him, that children point at him in the street, and that everyone makes him into an object of the public gaze:

Stares followed him everywhere. Pedestrians stopped and stared, or stared at him as they walked. Motorists slowed their cars and stared, and on occasion honked their horns to draw his face so they could stare into it. School-bound children hushed their mates and poked their fingers in his direction, wrapper-clad women paused in their front-yard duties and gazed after him, and stick chewing men leaned over their balcony railings to peer down at him.

For many readers, I suspect, this reversal will come as a relief. Blackass is the most unapologetically Nigerian book that American publishers have published in a long time, and as the “Afropolitan” has become an increasingly omnipresent strand of contemporary African literature, there has been a steady backlash, both against the Afropolitan as such, and against the entire category of African immigrant literature. Why are so many African writers actually writing about the United States and Europe?

It’s a complicated question, but it’s undeniable that, in the last few years, “Africans in the United States” has become a powerful—some would say dominant—narrative strand in “African literature.” Along with Adichie—who splits her time between the US and Nigeria—the list of young African writers who are or have been based in America is a pretty long list. Sefi Atta, Unoma Azuah, NoViolet Bulawayo, Chris Abani, Teju Cole, Laila Lalami, Dinaw Mengestu, Okey Ndibe, Taiye Selasi, and Chika Unigwe are all prominent writers whose most recent novel is set at least partly in the continental United States: Americanah, Edible Bones, A Bit of Difference, We Need New Names, The Secret History of Las Vegas, Open City, The Moor's Account, All Our Names, Foreign Gods, Inc, Ghana Must Go, and Black Messiah. To that list, 2016 will add Yaa Gyasi’s Homegoing and Imbolo Mbue’s Behold the Dreamers. (You could make a similar list for Afro-European literature, but I won’t bother).

Whether as cause or result, Adichie’s own success has been an important part of this re-opening of the US market to African writers. But while some would see her remarkable popularity as creating space for other writers, others would it as closing down the possibility of other kinds of narratives: to be an “African” writer, after Adichie, might mean to write a very particular (even singular) story. It would be ridiculous to blame her for this—though as I’ve argued, the “Afropolitan” is a very convenient scapegoat for the systemic forces they render visible—but it’s not surprising she’s so often a flashpoint for this kind of controversy. For my own part, I’ve struggled to understand why Jennifer Nansubuga Makumbi’s Kintu can’t seem to find a publisher in the West: the book is a masterpiece, an absolute gem, the great Ugandan novel that you didn’t know you were waiting for. But if you look at the Adichie-shaped space for African literature in the American publishing market, the question answers itself. The “we” that publishers dream into existence is far less interested in the great Ugandan novel than in the Last King of Scotland (or in the Americanah movie currently in production); I suspect that Jennifer Makumbi’s first book published outside of Africa will be a book dealing with African immigrants in Europe. “Afropolitan” writers like Adichie, Selasi, Cole, and Bulawayo are certainly not the cause of this insularity, but it’s easy to see why they get resented for their ability to bypass it.

If Americanah is an “Afropolitan” narrative—and Blackass isn’t—then it would be easy to set them in opposition to each other, to make Barrett the kind of novelist that Adichie has failed to be. It is tempting, after all, to hold authors responsible for fixing systemic problems like the whiteness of publishing. But we should avoid this temptation. For all of its obsessively local orientation, Blackass is a Nigerian novel about the Afropolitan fantasy, and about the painful reality of race: however perfectly it subverts an Americanah-shaped Afropolitan model, there is no antithesis without a thesis to invert. And if we linger with Americanah for more than a few minutes, we’ll start to notice what a profoundly Lagosian novel it is; even the title is a deeply Nigerian word. And if Blackass is such a deeply Lagosian novel, why is it filled with references to Kafka, Ovid, and Apuleius?

*

It’s easy to draw a contrast between Adichie’s romance novel about blackness in America and Barrett’s Kafka-esque parable about whiteness in Nigeria, or to note that while Americanah’s popularity is at least partly a function of its popular (and very feminized) generic conventions, Blackass is drenched with literary references to dead white men, starting with Kafka. In the same way that Barrett’s Love is Power, or Something Like That (2014) was often compared to European models (e.g., "Barrett does for Lagos what Chekhov did for Saint Petersburg and what Joyce did for Dublin"), there has been an abundance of commentary on Blackass’s Kafkquosity when it was first published last year in Great Britain: "Borrowing heavily from Kafka," “Barrett’s satirical update on Kafka’s The Metamorphosis” (or “Retelling of Kafka’s The Metamorphosis in contemporary Lagos”) is “deeply indebted to Kafka.” “Openly paying tribute to Kafka’s Metamorphosis,” this “cocktail of Kafka and comedy” is “Kafka for the Kanye generation.” It’s the first thing many of them mention, and often the last as well.

The best reviews usually come out long after the first reviews, and with the benefit of that perspective, James Reich has already observed that Kafka is just one of many literary reference points; the title, for example, is a reference to “the African author Apuleius and The Golden Ass,” and that’s only the tip of the iceberg. But the obsession with Kafka is symptomatic of a particular kind of readerly perspective, whose insufficiency is worth noting: we have a Nigerian novel about a Nigerian man’s superficial resemblance to a white man, and… we find ourselves remarking on the novel’s superficial resemblance to a white man’s novel.

Complaining about Afropolitans is a good way to blame writers for the insufficiencies of the literature, but there is also a profound literacy problem when it comes to African literature. We know how to read African writers when they are Chinua Achebe, when they write about the US and Europe, or when they riff on Kafka. But why has every reviewer paid so much attention to the epigraph from Kafka, and none—that I have seen—has paid attention to the epigraph from the “Three Elders” statue welcoming visitors to Lagos? What if that were the starting point for reading this novel? I don’t know what such a reading would produce, but I am aware that I don’t know (and I wish I did).

One of the only reviewers not to link the novel to Kafka—or even to mention him—was the Nigerian writer Ikhide Ikheloa. Likely because Ikhide was (quite characteristically) laser-focused on the ways that Blackass is using and riffing on social media, Blackass’s “debt” to Kafka was the very last thing that he wanted to talk about. Ikhide had less than no interest in placing Barrett back into European traditions that new authors “update” and “retell,” but remain “in debt” to the source from which they’ve “borrowed,” and to whom they pay “tribute.” Those metaphors tell you a lot, in the aggregate, about how we read African literature, if we see it as an offshoot of European traditions: thanks to the gift of Western Literature, Africans also have books and novel! Kind of! (You’re welcome, Africa.)

Instead, Ikhide reads forward:

The vast majority of contemporary African literature is now being penned digitally. To ignore that sea of writing is to distort the history and trajectory of African literature. The good news is that many writers are fighting back—and making a difference. One such writer is A. Igoni Barrett...he has done extremely important work on the Internet as a leader and a pioneer using that space to showcase his works and ideas and also advance the cause of African literature.

Ikhide highlights something that Blackass’s “debts” to Kafka can only overshadow: the novel’s deep and interesting engagement with social media, one of the most important social texts on which the Nigerian nation is being written. Not since Americanah have I read a novel that so organically incorporates social media into a fictional narrative, or which so adroitly imagines how the modes of self-writing that social media enables can be used to live in a world of white supremacist violence. In this way, like Americanah, Blackass goes far beyond simply including social media as an aspect of life in the world portrayed by the novel (though that is deftly done; taking place in Lagos, social media is as banal an infrastructure as telephones or the radio, and is presented that way). But just as Adichie did in Americanah, Blackass narrates and portrays its own development out of social media, a literary becoming that happens “online.”

If Americanah was (among other things) about becoming a writer, Blackass is about the writer becoming a reader. Relatively early in the novel, our protagonist not only meets A. Igoni Barrett himself, in a café, but after he piques the author’s interest with his unusual combination of white skin and Nigerian accent, Barrett becomes an important character in the novel, using twitter to track down Wariboko’s sister and eventually Wariboko himself. Wariboko’s story is not his literary creation, in this sense, but the story he is told—once he finds Wariboko—and listens to it. In the literal space of this meta-fiction, then, Twitter is the medium through which he eventually composes the novel which we’re reading (and in which he goes from an observing lurker to a full participant).

Adichie used blog-writing to imagine the messy, comic space of awkward identity-formation and desire; Barrett uses social media like Twitter to literalize the dream of becoming someone other than who you are, as well as to portray the often hidden cost of making that transformation real. Social media lets you be anyone you want. But being is one thing, as the author of the novel several times remarks; becoming is another. For Wariboko, being white is a matter of waking up one day and discovering that it has happened. But by struggling to become white, over the course of the rest of the novel, he illustrates the extent to which race is nothing so simple and coherent as a spectrum of skin color. And—if only latently, by implication—he comes to realize how much of what he was, as a black Nigerian, has been lost when he becomes, simply, a Nigerian (who is white).

Becoming white, for Wariboko, is a matter of understanding what it is that Nigerians are staring at, when they stare at him. It is also a matter of realizing what whiteness isn’t: in Nigeria, white skin is not an invisible backpack filled with privilege, though it certainly does create opportunities. When he was a 33-year-old, unemployed black Nigerian man, every door had been closed to him; his new self, by contrast, is inundated with job offers and propositions. He quickly finds female companionship and eventually gets himself hired to market how-to and business education books. But while his newfound identity makes him the subject of constant and continuous interest—as an oddity that can be valuable to those who know how to use it—his race is not really power, nor anything like that. In Nigeria, a white man is also, always, an outsider, and if his white skin is an asset, it is not always for him to use it. Whiteness, it turns out, is an opportunity to be used. The money, connections, and documents that make race a reality are very different things than the undisputable fact of skin color, and he has only the latter.

It’s not a coincidence that nearly every Afropolitan narrative seems to find its way back to race and to Africa; after lingering in America, which “smells of nothing,” the end of Ifemelu’s blogging is to return home, and to know it for the first time. Afropolitan narratives are never immigrant narratives, always resistant to stories about melting pots; Americanah never stops being a Nigerian word. Instead, the Afropolitan single story is about what money and connections and documents can’t transform, the point where dreams of metamorphoses meet the chill air of morning and the reality principle re-imposes itself. And when Furo Wariboko’s blackass comes unstuck from race, he discovers the flip-side of that racial coin: without gold, everyone’s ass smells the same.

Aaron Bady is a writer and recovering academic in Oakland, CA. Check out aaronbady.com and follow him on Twitter @zunguzungu.