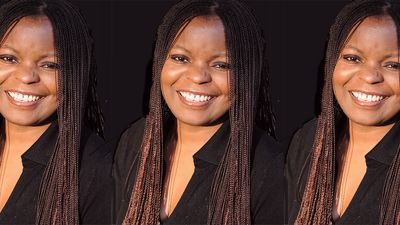

Petina Gappah On The Caustic Wit of Her Novel, 'The Book of Memory'

The Zimbabwean author speaks about the pleasures of writing in Zimnglish and using humour to make sense of the world.

Debut novelists are not renowned for having an assured voice. For the gifted and fortunate, more often than not, the first fruit is a taste of a greater harvest to come. With a much praised book of short stories in the bag (winner of the Guardian First Book Award 2009), Petina Gappah is hardly an apprentice story teller.

Book of Memory, her first novel, is about a woman called Memory who is on death row in Chikurubi Maximum Prison in Harare, Zimbabwe having been convicted of the murder of her adopted father, a white man called Lloyd Hendricks. To appeal her murder conviction, she has been encouraged by her lawyer to put down in writing events leading up to his death.

What she calls her “oral biography” flits between her childhood in a poor township, her later life of affluence as an adopted child and to her present predicament in a jail cell. Cleverly, Ms Gappah reminds the reader of the artifice of her narrative device “I thought at first that writing all of this down for you would be difficult…”

As narrator, Memory proves to be very good company, earnest but not too revealing, accepting of her fate but not paralysed by it. Memory’s one striking feature is her albinism. This would be vivid in a visual medium or in real life but not so much in prose form I have found. I complained to Ms Gappah about this in an interview conducted via email.

Memory’s albinism gives her a special distinction in appearance. Why did you choose to make her an albino?

For the plot to work the way that I conceived and constructed it, I needed my main character Memory to have a physical disability that is immediately visible. I needed her to have a condition that separates her from everyone around her, that makes her stand out. I would say more but I don’t wish to give the entire plot away!

Did you ever worry that this might relegate her other behavioural traits and quirks that you have ascribed to Memory

Not at all because people with conditions such as albinism are people like anyone else. The condition of albinism is first of all a medical condition. The only “behavioural traits” or “quirks” that a person with albinism would exhibit that are different from those of a person without the condition are things like staying away from the sun, using sunscreen, and other behaviours related to the condition, not to the individual person who has the condition.

The gravity of Memory’s predicament overrode her albinism so much that every time it came up, it felt like being introduced to it for the first time. Did you have a similar experience even as you worked on the novel?

I am so pleased you say that because that is the whole point of the character. Her condition affects how she is seen by others and how she reacts to the sun, it affects her eyesight and so on, it affects her health. It is a medical condition. It obviously has some effect on her sense of self, but essentially, what affects her sense of self are the circumstances in which she finds herself, the dislocation of the wrenching move from one home to another and being the only woman in the country on death row.

**

Gallows humour is not a democratic taste. Memory can mock her own death but I the Reader feel obliged to only laugh along in secret. She is admirably witty for a woman who is awaiting execution. It is one of the joys of reading her story, this wry way of seeing the world but it is not clear if this has been foisted on her by her impending demise, or if it predates her trial. A fellow albino from her childhood who tried to make a connection with her on the basis of their shared skin condition is mercilessly rendered as someone who “chatted endlessly about the novels he was perpetually peering at”. A Pentecostal evangelist’s curative power is said to make the lame walk, make the blind see and “the overweight experience instant weight loss. The short gain centimetres”. Catholic sisters are said to have heavy shoes and “equally heavy names”. An old neighbour is said to have been any age “from thirty-five to sixty”, a cruel and absurd but no doubt memorable description. All these and the other examples in the book amount to an acerbity that I found delightful.

**

Your caustic wit is on display all through the novel. Is this something you’ve worked on or does it come easy to you?

It’s hard for me to say whether my “caustic wit” as you call it comes naturally to me! I don’t know that it is that caustic or that witty, but I have always found that humour is the best way I have of making sense and coming to terms with the madness and absurdity of the world. I would rather laugh than cry. By laughing, am I implicitly holding up the English language as superior and those who speak it "properly" anything but?

As recently as 2013, Zimbabweans reiterated their acceptance of English by making it one of the official languages recognised under our constitution. This was approved in a popular referendum, so the idea that English is not “ours” is something that would come as something of a surprise to the average Zimbabwean who lives a life in English as well as his or her mother language. We inhabit English quite comfortably, I think, and we even have our own version of it, a version I call Zimnglish, which pleases me because English allows us to be connected globally while still retaining a strong sense of who we are as a people.

We learn from Memory that “there are no women in the mental ward". Does this mean that there women are not admitted into the mental ward or is that there are no recorded cases of mental health issues among the women in Zimbabwe?

This is simply because it’s a numbers thing, because there are fewer women, there are fewer specialised services available to them. In theory, Memory, the main character, should be separated from the rest because she is on death row, but that can not happen because there are less than 400 women in the whole prison, so there is greater fluidity between the categories. So women do suffer mental illness as much as men, but in the world of this novel, they do not have the specialised services they need.

**

Memory often talks about the legal aspect of her case with authority. She claims it is a result of her lengthy dealings with her lawyer and the courts. This is convincing enough but knowing that Ms Gappah is a practicing lawyer takes away some of that credibility. Here is an example of one of such passages:

“Mavis did not hang because the judges found extenuating circumstances in her case. Vernah Sithole told me about Mavis Munongwa’s was the case that set the legal precedent that a strong belief in witchcraft, like excessive alchohol or catching your wife in an adulterous coupling, could be considered extenuating circumstances in mitigating sentence, and could even go as far as amounting to provocation, which, more than mitigation, is an actual offence.”

A clutch of words like “extenuating” “provocation” “mitigating” and a phrase like “legal precedent” all packed in one paragraph in a book written by a lawyer turned novelist can only point to her training. One approach is to accept this as true. Another is to distance oneself from such acquired technical language so as to maintain ones integrity as a novelist. This says something about the false but persistent belief in the purity of an artistic calling which ought not to be soiled by borrowed knowledge from other specialist fields, even when it heavily depends on them. A novel like The Book of Memory relies not only on a legal precedent (punishment for a crime) but on the entire machinery of the law (Memory’s arrest, trial, conviction and pending execution) for it to function in the way it is intended. But it is also in its best interest not to be seen as being wedded to legalities or even worse, to source its vitality from it.

**

As a lawyer, did you have to be careful not to weigh the book down with specialised knowledge given your own specialised knowledge?

I know nothing about criminal law beyond what I in studied at university 20 odd years ago as I never actually practiced law in any domestic jurisdiction. It would be a very bad idea to ask me to defend an actual person who is accused of a crime because my field is international trade law, where I advise governments, which is very different from defending an accused person! So I found that I had to do a lot of relearning and research to make the characters sound half way to competent. So the only special advantage I had as a lawyer was possibly knowing where to look for what I needed.

Sabo Kpade is a sifter for the SI Leeds Literary Prize 2016. He's been shortlisted for the London Short Story Prize 2015 and was a finalist for the Beeta Playwriting Competition 2015. You can follow him on Twitter @Sabo_Kpade.