Maglera Doe Boy’s “God Is Power” Music Video Turns Township Grit Into Cinematic Art

Set in Kanana township and styled like a Roman noir, Maglera’s latest video is a mythic origin story that reframes kasi life through sacred symbolism and surrealist visual language.

God Is Power shows the township as a place of struggle, style, and deeper meaning.

On his latest release, South African wordsmith Maglera Doe Boy adds another layer to a growing visual legacy, one that favours intimate social realism over glossy escapism.

“God Is Power” aims for the clouds and ends up cracking the sky. It’s a sublime statement of purpose, towering in its execution and refreshingly original in how it pays homage to the classics, while attempting to introduce new narratives to the canon. This is kasi filmmaking gone neo-noir, set against Fiji Mageba’s sweeping, string-laced sonic opus, and featuring burningforestboy’s hauntingly beautiful, reverb-drenched vocals.

The song “God Is Power” comes from last December’s Maglera Tapes – the genre-disrespecting, form-bending project that blurs the lines between lavish uptown raps and first-person township memoirs. The conditions of the township can’t be ignored. They remain outposts, living relics of Apartheid’s brutal spatial engineering, designed to erase Black and Brown South Africans from official visibility while keeping them close enough to fuel the economy and generate billions for the state.

But in the hands of co-directors Maglera Doe Boy and Big Shark, the township is ground zero, a training bay to launch into bigger and better things. It’s transfiguring and transformative, a crossroads as sharp as the realities portrayed in some scenes: a knife duel over here, a gun pointed to the face over there — all part of daily life in the Kanana, Orkney (Greater Matlosana, also known as Maglera) township that the artist grew up in, and where the filming took place.

“Originally, I wanted to call this song ‘Power Is God,’ because of how society views and perceives power. People have different [kinds of] power; you have influence, you have riches, and you have religious power,” he tells OkayAfrica. ‘God Is Power’ was more fitting; he didn’t like the idea of people saying ‘power is my God.’ “[It means that] your proximity to your God, your proximity to sovereignty and purity from spirituality is powerful,” he says.

A big part of what informs Maglera Doe Boy’s lore, besides lived experiences, is books. From the study material his parents, who were teachers, used to read, he learned about the expanse of empires.

“[Reading the study material] made me love a design that is very sacred for my art. Many of those books referenced Shakespeare, and some of the most prominent writers primarily discussed empires and those eras. So I’ve always had a liking to that,” he tells OkayAfrica.

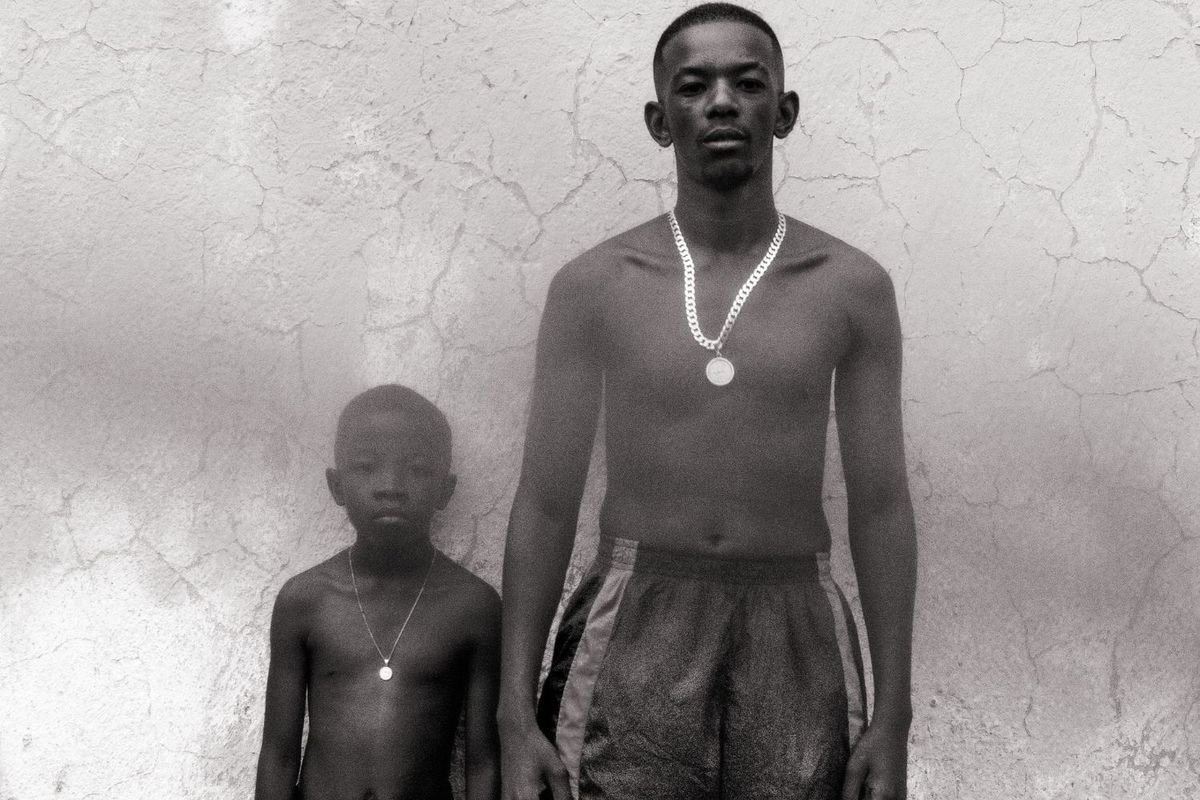

There are past vlogs on YouTube that document similar characters in his hood. The surrealist montage of “God Is Power” feels like an addition to a story that is still getting told. It features the protagonist Warlord (played by his nephew, Lonwabo) versus Scorn, his spiritual opposite, and recasts township life as a Roman Empire-inspired epic.

When Maglera Doe Boy raps that “the township is the new Gulag, just a different cage,” it’s to the visual accompaniment of still photography – an MF DOOM-esque mask in one frame, five figures frozen mid-pose, evoking both township fashion and mythological archetypes in another, donning leather regalia, balaclavas, layered jackets, patched jeans, face obscuring – very rooted, but also very otherworldly, like a painting by one of the renaissance era greats. These characters are more than narrative devices, but also symbols of a young boy’s inner war, and a reality shaped by the harsh contradictions of township life.

“I want [kids from Kanana] to feel that they’re seen,” says Maglera Doe Boy.

Photo by iindman

The artist’s childhood streets are turned into cinema, and it’s something that warms his heart. “I love it, because it also shows people where I come from and why I speak the way I speak about Black people,” he says. The video also shifted his understanding of his past. “It made me very aware of things I felt. That kid (Lonwabo) is me. Seeing him re-enact moments that I’ve had in the township, and things that I’ve seen, made me feel very deeply about this idea.”

“I want [kids from Kanana] to feel that they’re seen. The things that we saw – especially my generation of kids, who saw that type of stuff the most, because that township was in a very dire place. I still think it is – all townships are. Because it’s just that congestion and that cesspool that is now a portal to the darker things that happen in the hood, which is what I wanted to show people. But more than anything, show them in-between all of that, I picked my power, and my power was making money, and my power was [for] remembering God.”

- South African Rapper Cassper Nyovest Drops New Single "018" with Maglera Doe Boy ›

- Review: Maglera Doe Boy’s Latest Album Is An Engrossing Love Letter to South Africa's Street Corners ›