A Not So Different World: An African Student's Love Letter to American HBCUs

In this personal essay, Cameroonian writer Kangsen Feka Wakai recalls his time as an African immigrant at a Historically Black College.

DIASPORA—I sat with Wanyama on the staircase in front of the Granville Sawyer auditorium watching a group of girls giggling in the distance. We were both hoping against hope that we might somehow catch their attention. Maybe, we fantasized, they’d give us their numbers or invite us to the Kappa beach party in Galveston.

So it was a mild shock when two of the girls broke off from the pack and started walking towards us laughing. I focused my attention on the shorter of the two, her bright teeth shining even from the distance.

When they were within spitting distance from us, she said, “Dayyum, y’all some dark chocolate niggas!”

“Fine too,” her friend chimed in.

A few shades darker than me, Wanyama—an aspiring painter, six-feet-three wearing sunbaked brown twists—had been on campus a semester longer, so he spoke to them.

“What’s up with y’all?” he asked, his Nairobi lilt shining through.

I remained silent, worried that my expression would betray my anxiety.

“Nothin’, what y’all doing here?” responded the taller girl with the calmer disposition.

I forced a smile, “Hey!”

“We chillin,” Wanyama said.

The shorter girl, arms folded across her chest, curled her lips in mock disapproval. Lips still curled, she leaned sideways, left leg forward.

“Why y’all so black and where y’all from?”

“Cameroon.”

“Kenya.”

“Holla at your girls,” the shorter girl said.

Wanyama did most of the talking. They were freshmen from the same high school in Kansas. The shorter one lived in a dorm while her friend lived with an aunt off campus. She hated the bus ride. Neither of us had cars.

Between pauses, I mined for the appropriate lexicon to translate my new friend’s posture and tone, which despite its foreignness felt familiar.

We parted ways with our new friends, delighted. For me, another boundary crossed.

When I received my admission letter from the University of Wisconsin, Whitewater at home in Cameroon, I had never heard of Texas Southern University nor had I heard of Historically Black Colleges and Universities. But after surviving a midwestern winter, I did not need much convincing when a friend who was enrolled there suggested that a transfer might not be that complicated. She pointed out it was a quarter of the cost at Wisconsin, and warmer than both Bamenda and Yaounde—the cities of my youth.

“Dr. Perkins, the international student admissions director will practically drag you in,” she said.

She was right. Within a matter of days an admissions package arrived in my brother’s mailbox. One look at the beautiful black faces smiling at me, and I had cast myself as the protagonist in my rendition of “A Different World” where I navigated the school’s cafeteria, hallways and residence halls like Dwayne Wayne without the flip up sunshades.

TSU was not the Hillman College of Bill Cosby’s imagination. Though aspects of it seemed recognizable—unfolding like scenes from the lives of Jaleesa, Whitney and Ron—it lacked the coherence of a scripted television show intended to normalize the lives of African-American strivers. Hillman College did not prepare me for the barnstorming of bowtie wearing Black muslims, dreadlock wearing Hebrew Israelites, fatigue wearing recruiters and student preachers plying sermons on the yard.

On the surface, nothing about this shady campus in the heart of Houston’s Third Ward revealed the giants that had strode its cobblestone pavements. While nothing about the cluster of students cloistering the DJ in the “pit” playing a chopped version of Southside Playaz’sYou Gottus Fuxxed Up by Houston’s own Screwed Up Click hinted that a Chloe Anthony Wofford—now known as Toni Morrison—once walked the hallways of the Thornton M. Fairchild building as an English instructor; if one looked closely, the evidence pointed to a far richer narrative than what met the eye.

In fact, what did meet the eye were clues to the oratorical roots of political luminaries like Barbara Jordan and Mickey Leland, their portraits adorning the walls of the Traditional African Arts Collection gallery leading to the Charles F. Heartman Collection on the ground floor of the library.

And for those who listened closely enough, what met the ear was the legend of how an unknown affable defensive end named Michael Strahan who used these grounds to write himself into American football lore.

When I first came to Texas Southern University, I didn’t know the stories about how segregationist tendencies, a $2,800 dollar loan from the Houston Public School Board and the need to feel the vacuum in the city’s growing colored professional class had conspired during a summer seven decades earlier to create the Colored Junior College from which the Texas Southern University was born.

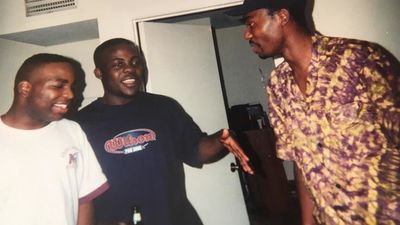

Instead, dazed by the infinity of beautiful Black women in our fields of vision, my friends and I mostly idled our days away on the wide front staircase of the Granville Sawyer auditorium gazing the throngs of students crisscrossing the courtyard.

Our anonymity assured in this ocean of mostly African peoples, we felt a measure of protectiveness in a city we were too aware was still coming to terms with its new identity. As Houston changed so did TSU, but what hadn’t changed was its core mission to train those whose historical exclusion from white society had once been the law of the state and city.

For those of us with no mother tongue to claim, or those with one but no one with whom to speak it, TSU provided a moment and platform for us to forge a new language out of the Yoruba, Swahili, Sheng, Pidgin, Igbo, Cantonese, Urdu, Hausa, Malinke, Wolof and Amharic that animated the walls of the Ernest S. Sterling Student Life Center. A new language that allowed us to transcend our individual, ethnic, class, linguistic and national selves. After all, on this landscape, the prominence of the “tiger” flag rendered invisible our national proclivities and flags instead binding us into a common narrative that married our collective triumphs with past and present struggles.

Weeks after the Galveston beach party, which we were too broke to attend, Wanyama and I reconvened at our favorite staircase to observe the runway. We laughed at ourselves for our lack of funds and our high-flying fantasies of taking our new friends out on dates.

We dissected Mos Def and Talib Kweli’s lyrics in “Black Star;” debated the cultural significance of Jay Z and DMX in a post Tupac-Biggie world; made a symbolic toast to Omar Epps and the prominence of darkskinned brothers. Then we dreamed of New York and LA. We always dreamed of somewhere else.

Kangsen Feka Wakai was born in Cameroon. His writings have appeared in Chimurenga’s The Chronic, Transition, Callaloo and Post No Ills Magazine. He lives in Washington, D.C. Follow him on Twitter @KfWakai