How Sudan Relies on Online Banking and Digital Payments Amid Currency Crisis and War

Seven months after Sudan’s partial currency change, citizens still don’t have banknotes for their daily transactions, and are increasingly turning to digital transactions and electronic banking to manage everyday expenses.

In January, Sudan’s army-backed government issued a new 1,000 Sudanese pound banknote, sending people into panic and the banking system into chaos. The streets of Port Sudan, the de facto wartime capital, were filled with citizens scrambling to file cash into their bank accounts, which should then be turned into the new currency.

“The process of exchanging old currency for new proved to be highly inefficient and cumbersome,” Dr. Mohamed Osman, who works at the Bank of Sudan, tells OkayAfrica. “A very short timeline was set for the exchange, leading to overcrowded banks, a severe cash shortage, and a general paralysis of commercial activity.”

The first images of this political decision were long lines of people who would sometimes wait outside their bank branches for days with no success exchanging their money. The second group was the same disbelieving citizens who were left without cash when the government realized that the banks could not print enough new notes to replace the old ones.

As a result, grocers, gas stations, and rickshaw drivers no longer accepted the old currency, but citizens did not have the new one to pay for necessary amenities. Banks began relying on digital currency, and in an unexpected turn, a country ravaged by war underwent a rapid transformation towards online banking.

Photo by AFP via Getty Images

Employees count bills at the Central Bank in Port Sudan on July 23, 2023.

“Following the deterioration of Sudan's economy, the government implemented a plan to bring money back into the banking system,” says Osman. “This was crucial because, since the Omar al-Bashir regime, most of the circulating currency had been held by individuals. Recovering these hoarded funds was seen as a potential way to revitalize the economy.”

This was the official narrative, but replacing 500 and 1,000 Sudanese pound banknotes (worth around $0.25 and $0.50 respectively) with new ones was widely understood to be a political strategy by the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) amidst their ongoing war with the Rapid Support Forces (RSF).

“Another objective of the currency change was to recover stolen balances and funds in Khartoum and Al Jazirah states and return them to the banks,” says Osman. After the RSF had looted banks, the SAF wanted to regain control of Sudanese cash flows, implementing a currency that could not be used in RSF-controlled states.

Even before this war divided Sudan into a two-currency country, it caused the world’s worst humanitarian crisis, widespread famine, and soaring inflation. From 500 Sudanese pounds to the US dollar in April 2023, it just reached 3000, showing no sign of stabilizing despite the new bank notes.

“The people of Sudan started a revolution against Omar al-Bashir because the bread price was raised from 4 [loaves of] bread for one pound to 2 [loaves of] bread for one pound,” Almuthanna Abdulmoneim Alryeih Abdulgabbar, an electrical engineer from Port Sudan, tells OkayAfrica. “Now they buy one [loaf of] bread for 150 pounds.”

Photo by Mujahed Sharaf Al-Deen Sati/AFP via Getty Images

Sudanese buy bread from a bakery in the capital, Khartoum, on October 11, 2021

Presently, most Sudanese in areas controlled by the SAF rely on bank apps for their money transactions. The Bank of Khartoum’s “Bankak” is most widely used, but other banks have created their own apps, such as Faisal Islamic Bank’s “Fawry” and Omdurman National Bank’s “Ocash.”

“[These apps] were initially not accessible to everyone and performed poorly,” says Osman. Once again, people were crowding around their bank branches, waiting for hours to simply activate the apps.

Engineer Muhannad Hassan, who developed Ocash, explains to OkayAfrica that these issues stem from the banking systems, not the applications’ design.

“Obstacles for the user in using the application generally arise when the application system is updated,” he says. “This is when the user faces difficulty completing transactions and transfers through the application, as the update originally comes from the bank's databases.”

Accordingly, whenever the system is updating or down, people cannot pay for necessities. In a war-torn country, this reliance on digital banking puts citizens, who are already suffering in the economic crisis, in an even more fragile position.

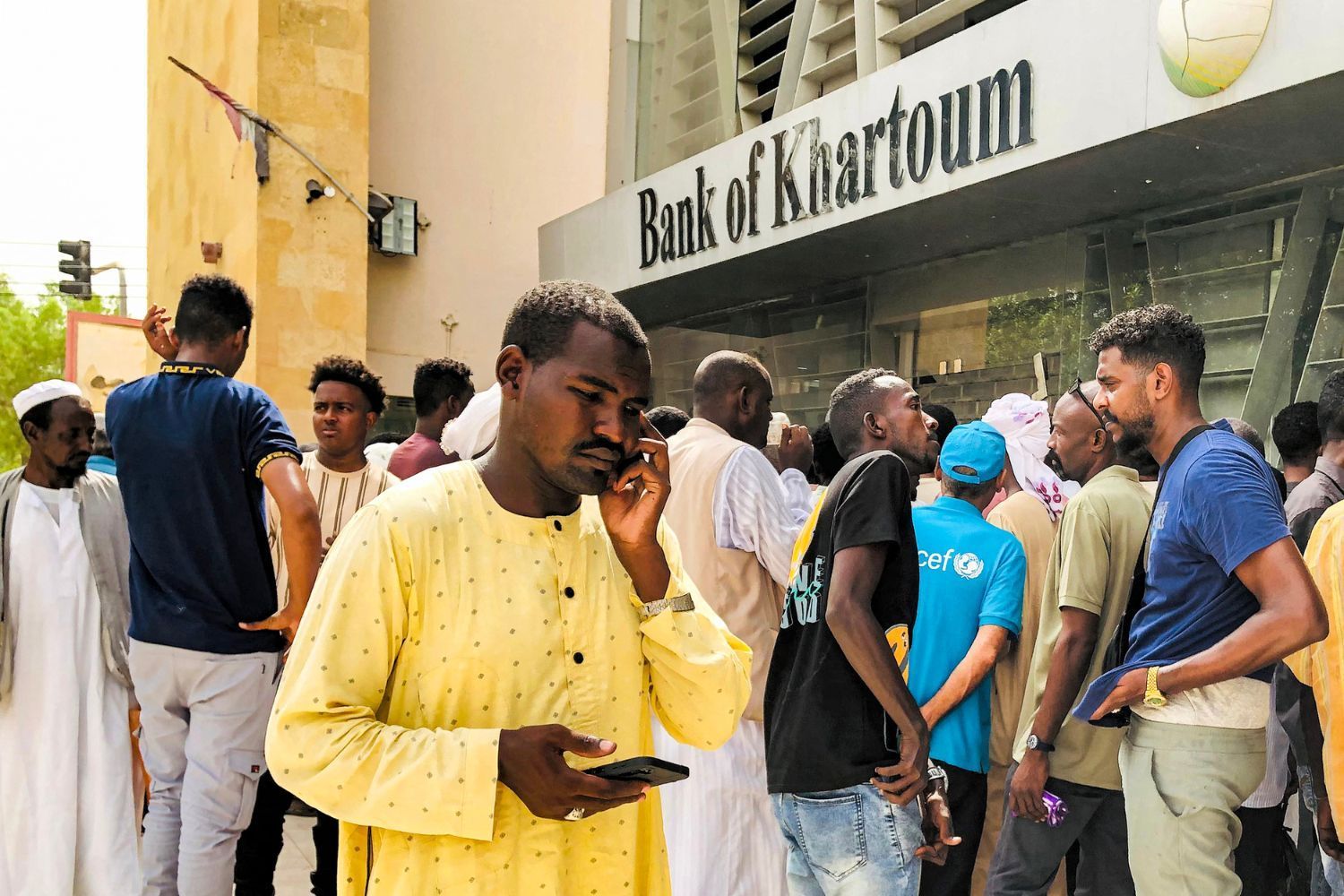

Photo by Almuthanna Abdulmoneim Alryeih Abdulgabbar

People standing outside the Bank of Khartoum to activate Bankak.

“Amidst this changing currency landscape, a new type of trade has emerged: the exchange of cash currency for balances transferred via applications, with financial benefits,” says Abdulgabbar. “For example, if you want to receive 100,000 Sudanese pounds, the profit from the transaction could be up to 10,000 Sudanese pounds, where you transfer from any application and receive the amount in banknotes.”

This process, which Abdulgabbar calls “nothing but plain usury,” is forbidden in Islam, Sudan’s primary religion.

He agrees that moving banking to the digital sphere is good in general, but says that it was implemented at the wrong time in Sudan, and for the wrong reasons. Like many others, he believes that the currency change’s purpose was to benefit the army, not the people who have nonetheless adjusted to this new system.

Osman strikes a more positive note. “Despite the initial challenges, there has been a clear improvement in the transaction system since the initial period, with the process of opening bank accounts becoming easier for the general public,” he says.

- Here is Everything We Know About The Ongoing Sudan Crisis ›

- Music, Identity & War In Sudan: Beats Of The Antonov Debuts Online ›

- How Football Has Carried Sudan Through Empire, Strikes, and War ›

- Sudan is on the Verge of the World’s Largest Hunger Crisis: Here’s How to Help ›

- Will US Sanctions Have an Impact on the War in Sudan? ›

- What It’s Like To … Be a First Responder in the Sudan War ›

- Sudan Can’t Wait ›

- ICJ Dismisses Sudan’s Case Against the UAE ›