African Sci-Fi Takes Off With Reissue of Zimbabwean Novel

Masimba Musodza's Shona-language work blurs the line between science-fiction and fantasy and is based firmly in local mythologies.

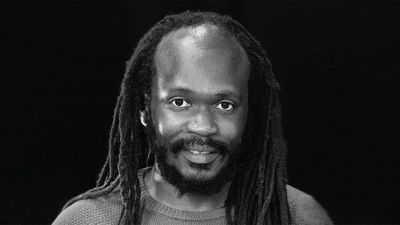

Masimba Musodza is a refreshingly unique writer from Zimbabwe. His small but eclectic body of work, so far, redefines many aspects of Zimbabwean literature. He infuses most of his writing with the spirit and ideals of Rastafarianism and from book to book experiments with style and genre.

In 2011, he published what is possibly the first sci-fi novel in Shona, Muna Hacha Maive Nei. The book is being re-issued after growing interest in speculative fiction written by African writers. It is a genre beleaguered by a lack of diversity which is a problem that exists throughout the spectrum of speculative fiction. Mainstream culture tends to codify speculative fiction fandom as a white phenomenon.

The most speculative element of this book is in its language. Not that this novel will be universally appealing, it’s a little too esoteric, a little too culture specific. The Shona peoples, for whom the book is targeted, are mostly found in southern Africa.

Still, it’s mere existence is significant. Musodza prefaces the book with an introductory essay in Shona that provides historical precedents in speculative fiction in the Shona culture which is firmly rooted in intricate mythologies. It’s debatable whether Musodza’s book qualifies as speculative fiction or fantasy, not that it matters very much.

Musodza’s book straddles the liminal space between the otherworldly and ordinary village drama. This is a familiar trope in Shona fiction. The science aspect of the book is suggested in the bio hazards that threaten a village river, for centuries a symbol of the village’s livelihood and existence. Indeed, the link between black struggle and the resilience of the black imagination is evident in early Shona writings published in the 60s.

Independent filmmaker M. Asli Dukan whose documentary Invisible Universe about the contributions black people have made to speculative fiction throughout history right up to the present day explains:

The interesting thing about mainstream speculative fiction is that it really kicked off around the same time that Europe started imperialising the world, especially Africa. You can read these stories set in past versions of the future and notice parallels between the way some of these books talked about aliens and the way that colonisers at that time would talk about Africans. In my mind the origins of the genre go hand in hand with the origins of white imperialism and white supremacy. It's hard to separate the two. It's carried on to this day, because it's embedded within the genre.

There is no doubt that Musodza demonstrates a remarkable flair for Shona and overturns the notion that it is not possible to write “complicated stuff” in vernacular African languages. He credits Ngugi’s seminal text Decolonising the Mind for deepening his affinity to his mother tongue, Shona. Ngugi himself recently had a story, The Upright Revolution, he originally published in Gikuyu translated into more than 30 African languages by a collective known as Jalada Africa.

Under strongman Robert Mugabe, 92, Zimbabwe’s future remains so uncertain that speculative fiction can, to some extent, help explore the multiple futures/pasts of a country still in flux. Speculative fiction provides an imaginative distance that could help cut through the political cringe that blights Zimbabwe’s tiny local fiction readership. Historically, Zimbabwean literature is largely grim, weighty and too serious to offer pleasure or entertainment. Musodza’s novel still acknowledges and engages with the country’s troubling history and the grotesque inequality, but it does so without holding on to the past.