ÌFÉ Mixes Santeria With Caribbean Synth-Pop To Create Something Wholly Original

We speak to Otura Mun about how he mixed his Afro-Diasporan/Yoruba religious practices with the music of the Caribbean to create ÌFÉ.

ÌFÉ is a band from Puerto Rico that just dropped one of the most anticipated records in the Caribbean music scene this year, their debut album IIII+IIII—pronounced Ejiogbe . It features innovative sounds that you may have heard before, but in very different configurations.

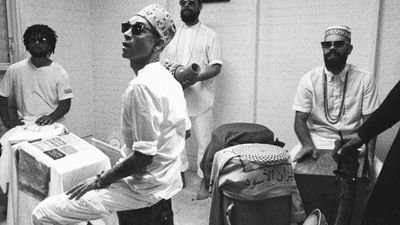

ÌFÉ is the project of Otura Mun, an African-American hip-hop and dancehall DJ who moved to Puerto Rico, became the DJ of legendary reggae band Cultura Profética, started his path to become a priest in the Yoruba-Caribbean religion of Santería, changed his name to fit his new faith, learned to master the Afro-Cuban rhythm of rumba and started a band that plays ancestral music with contemporary sounds.

We had a conversation about all of this and much more.

How did you end up in Puerto Rico?

I don't believe in coincidence, but it looked a lot like one. I was studying music in Texas in the early 90s, and around 1997 I was flying back to Indiana, which is where I was born and raised. The airline messed up one of my flights and they gave me a voucher that was good for a few destinations. I really wanted to go to Jamaica at the time, I was a hip-hop DJ and a dancehall DJ, and I was really into Jamaican music at that moment. But I let the ticket almost run out, and it was good for a year. So I called after eleven months and wanted Jamaica and they didn't offer that, and I asked them where in the Caribbean they went and at the time they said "St. Thomas, St. Croix, Puerto Rico," so I asked for St. Thomas, they told me it was booked solid. I asked for St. Croix, booked solid as well. And so my last option was Puerto Rico. So I just hopped in a plane, I didn't really know where I was going. I took 150 bucks for two weeks

When I got there I was looking for some sort of youth hostels which they have now, but they didn't back in the day and so the cheapest place to stay was a hotel for 20 bucks a night. So I ended up sleeping in the street for the first week. And I was ok with that. I was 22, I brought my skateboard and a bunch of mix-tapes to trade with people. I had a great time. San Juan had a great music scene and it was more lenient about drinking outside, so I ended up hanging out with people most of the day. I also met a Spanish exchange student who worked in a cafe I used to hang out a lot, and she let me stayed in her place for a week, with the condition of not speaking to her because she was about to leave Puerto Rico and she said she didn’t have room for more people in her life.

So I spent two weeks there and went back to the States. And in 1999 something happened which make me feel like I needed to get out of the United States. I really enjoyed the sense of freedom that I experienced with the young Puerto Ricans that I met in my first trip. I loved their lifestyle and I wanted to live that.

Also, in the US we have what for me amounts to a racial caste system. Everyone defines themselves racially first, and we built our identities from there. So being African-American, I felt that I knew the black experience quite well, but I didn't really know too much about Latin culture, and I also thought that I had a language barrier. I wanted to learn Spanish to create a cultural bridge to cross eventually at will. So I moved to Puerto Rico in 1999. I took a couple thousand bucks that I made at a going-away party that I threw in Dallas and just moved out there with my two turntables and a bag of clothes, couple crates of records and just sort of made a new life for myself from the start.So you got your start there DJing?

Yeah, because I had already been making a living doing that for a couple of years in Texas. And it was easy, because as a DJ I didn't have to say anything to anyone, I just played the records and that was that. When I got there, I was playing hip-hop and dancehall and there were very few people that were playing NY and LA style underground hip-hop and dancehall reggae. I found there was a class distinction there: the people that were into hip-hop were into it because they were bilingual, or because they thought that there was something intrinsically better about hip-hop in English than in Spanish. So I made a living immediately, but I couldn't get a job in Puerto Rico if I just spoke English, I had to be able to speak Spanish, and the way I got around that was DJing.

I was entering every record store in the first few weeks, introducing myself and meeting people. I was a really good turntablist and they had never seen anybody come and scratch on that level before, and so I immediately got booked in a few places. The music scene in Puerto Rico is a small world, so in a gig I met the guys from the reggae band Cultura Profética. They saw me perform and they invited me to start touring with them. I ended up being part of their touring act for their second, third and fourth records. And then recorded on a few records. I started travelling around the island with Cultura, we basically played every city that was on the island and then I started travelling internationally with them. And that was when I decided I wanted to double-down on my own music and started producing other singles.

How did you find Santería?

When I moved to Puerto Rico, I DJed at a millennium party in St. Thomas, in the U.S. Virgin Islands, and there was a group of rumberos from Puerto Rico that were called Grupo Carabalí and there were also a Yoruban dancer and a Yoruban singer that were from Nigeria playing there. Most of the rumberos that played with Grupo Caravalí were santeros and, in fact, the guy that I first saw playing the batá drum and singing to the orishas ended up becoming my rumba teacher.

It was very powerful for me to see these Puerto Ricans playing because they were doing that in the face of Nigerians who spoke Yoruba and understood the prayers and songs that they were singing, and the Nigerian was blown away, he had never seen anything like that before. He told these guys: "Look, you guys sound like my great-great grandfather. I recognize you—your accent is his accent.”

To be able to see a sort of straight line of our African heritage in this religious practice was very powerful for me. To see that this language was able to survive the middle passage and still be intact was just amazing to me. We often, as African-Americans, think about Africa in an abstraction, as opposed to having something with us that's just so obviously African. So this was just amazing to see. When I saw that in 2000, I knew that there was something there for me, but I also felt that it required a level of dedication and commitment that I was unable to submit. So I just let it be.Later on, say around 2012, I had finished producing some albums for some people in Puerto Rico and I didn't really owe anybody anything anymore, I was a free person, I packed up all my stuff and I was planning to leave Puerto Rico. I went to travel in the States for a little bit and I thought about what I wanted to do with my life. I had always wanted to learn how to play rumba. It was a music that I loved but, once again, I felt that it was going to require a level of dedication that was going to be all-consuming.

But this time I felt that I had my life very much in control in a physical sense. I had a good job, I had an apartment. I felt like I had these things that people want in life, but at the same time I felt that there was an invisible world that existed that I didn't understand and I was unaware of how to access. I felt that the Yoruba practice was a way with which I could begin to discover or understand that invisible world. So I thought: "ok, well, I'm going to dedicate my personal life, my secular life to the study of rumba” and so I went back to Puerto Rico and I just started practicing from 9 Am until 9 Pm, and I did that for six or seven days a week for maybe six or eight months.

During that same time, I began to consult with a babalawo [a priest in Santería], who later became my padrino in Ifá [godfather in the faith], and I began to study and discover the religion through consulting Orula [the orisha of divination] and through my padrino. I began initiating on different levels inside the religion and in 2014 I went through an initiation called "Mano de Orula" which is an initiation where they tell you who your patron orisha is. In my case, my patron orisha was Oshún, so I'm a son of Oshún. They also told me that I also had to pass over to Ifá, which meant that I needed to become a babalawo.

In 2015, I went to Cuba and went through that final initiation to become a babalawo. The best way to explain it is that it is a spiritual rebirth, so my purpose in life from that initiation changed from one of being a regular man to being a babalawo and understanding my life's mission as being a servant. I'm here to serve mankind and help people through Ifá. It's my job to study Ifá and a good servant, and a good servant means a knowledgeable one. I'll be at that for the rest of my life. It's a huge task, but one that can be achieved by working with your elders.

Why did your change your name to Otura Mun?

Otura Mun is my name in Ifá, every babalawo has a name in Ifá, and that name in Ifá corresponds to their sign in Ifá. There are 256 sings of Ifá and my sign is Otura Iroso. And Otura Mun is short for Otura Iroso. The whole idea is a way for us to immediately understand something about the other person. It's also a way for us to pass knowledge to each other. So, I meet an older babalawo and I tell them that my sign is Otura Mun, he's going to tell me something about that sign, and he's going to want to know that I know something about his sign as well. It’s like a scholarly sort of exchange where you are going to learn something, hopefully.

So, everyone who shares your sign have the name Otura Mun?

Yeah. There are only 256 possible signs, so there are a couple of people who follow me on Instagram that are also Otura Mun. The title of our record, for example, is "Ejiogbe," which is another sign in Ifá, it's the first sign. And, coincidentally, one of the members of the group, Rafael Maya is a babalawo and his sign is Ejiogbe.

And why did you choose that sign for the title?

I chose it because this is our first expression as a group and Ejiogbe is the very first sign on Ifá. It's the king of all signs, it's the starting point. It's a sign that, when it comes out in divination, one of the things that's indicating is spiritual awakening. Another thing that it indicates is coup d’etat, it's talking about state overthrow and the change of the guard.

Literally, the prophecy says "rey muerto, rey puesto" [“the king is dead, long live the king”], so there's going to be a switch. And it also talks about separation, because the sign looks like two parallel lines that never meet. So if you look at the front of our record, you see these two hands that are up and then there's a cross in the middle. That's actually a physical representation of what that sign looks like. The two hands up are also a political symbol as well. And I thought that it was a really good starting point from a philosophical end: this is the beginning, there are elements of this moment that I think are very important inside of that sign.

Also, for reasons that are personal, that sign is very important sign for me as a babalawo. It was part of a larger prophecy that I received in Cuba. Ejiogbe was going to be an important sign for me immediately after my initiation.

It's funny, because every year the babalawos in different countries get together and they devine a sign for their countries, and so the sign for Cuba this year is Ejiogbe, that's the sign that rules Cuba this year. I think that's an adequate sign for them as well, definitely talking about separation and political change of the guard.

Speaking of meaning, what does ÌFÉ mean?

Ìfé, the word, in Yoruba can mean "love", but it can also mean "expansion." I saw the word inside of the word “Life” like by noticing the LIFE Magazine logo on a photo that I particularly liked. I do most of the graphic design for the music I produce, and when I saw the word “ÌFÉ” there, I saw red and white, which are the colors of Changó [the orisha that is the owner of music and dance]. So I tried to think what was Changó trying to say to me here.

I was thinking about the power of Changó in music and in my life and then I saw that if you took the "L" out of “LIFE,” you get “ÌFÉ.” That to me was a powerful statement and a powerful beginning place. This happened in 2012, before I began to develop the music for ÌFÉ, but I knew I wanted to make a project and I was looking for a place to start. So I started with the word. I tried to imagine what "love" and "expansion" would sound like. How would you play that music?

How did that turn into the music of ÌFÉ?

I knew I wanted to make music that used improvisation, but spoke in the language of the moment, of today. And that's something that I like about Jamaican music, dancehall specifically, they use the sounds of today. I wanted to find a kind of music that I could use that allowed me to improvise as a musician, in the same way you could do that with jazz.

You don't have to know the rules of jazz composition to enjoy it, but if you do know the rules, then the conversation is a on a very, very high level. I wanted to work and rework this conversation inside ÌFÉ. I'm moving between Yoruba, Spanish and English, but I'm trying to purposely make something that would be inclusive for anyone whose base language is any or none of those. They should be able to understand the rhythm, which is also a language.

And I felt that rumba was the music with which I could do that. But I didn't know how to play rumba. That’s why I decided to dedicate a couple of years of my life to learning how to play the genre. Then, in 2015, I bought all the gear to make ÌFÉ, because then I realized that what I was going to do is was to take rumba structure and then drill holes in the drums and make the drums electronic so I can sit anybody down who knows how to play rumba and they can play inside of the structure that I want to play, but I can change the sounds, as well as the reason why we're playing.

From there, I started calling musicians. I called Rafael Maya, Beto Torrens, Anthony Sierra, and Yarimir Cabán, who are incredible musicians on their own, and also are basically the core of ÌFÉ, that's who I'm traveling with, that's who I'm recording with and that's the group onstage.

How do you decide the languages, both spoken and musical, of your songs?

Between English and Spanish, I often don't even realize what language I'm speaking, so I'm comfortable in either one, but uncomfortable in the same bracket, if that makes any sense. Because of the years that I dedicated towards learning Spanish, and sort of stopped speaking English, my dexterity and my eloquence in the English language took a dive, while my facility in Spanish started going up.

House of Love, for example, was the first song I ever wrote, and I wrote it in Spanish. I guess I made that conscious effort to do it in Spanish, because I felt that that theme was very tied to my religious practice. And that’s almost all in Spanish. All my prayers are in Spanish, all of my daily rituals are in Spanish. The theme of the song dealt mostly with my relationship with my ancestors, so I thought about the ritual themselves in Spanish and just wrote in that direction.

But it was quite a challenge because I don't read poetry in Spanish, I don't have the vocabulary yet to be able to understand it. So what I tried to do was to say as little as possible to get the ideas across. Try to be as honest about the sentiment that I wanted to portray.

For example, the first line is "Dime hermano, soy tu servidor," like "Tell me, my brother, I'm your servant." I'm personally talking about my brother who passed away, but if I'm telling my brother "I'm your servant", that could be interpreted as well as "brotherhood". And being there as a friend or whatever.

In the second line I was still talking about him, but I changed the ending of the last word from a masculine -o to a feminine -a, so it became "te adoro, eres única" [“I love you, you are unique”]. It opens it up for interpretation. So I pushed that one in Spanish. "Umbo" was maybe the first one I did in English, but it mixes with a lot of Yoruba.

Do you speak Yoruba, or do you know it more from your religious practice?

I'm not a Yoruba speaker, but a lot of the religious practice is in Yoruba. For example, there's an obra that I have to memorize as a babalawo, “Ebo de tablero,” which is a sort of cleansing. It uses something like 70 prayers and songs in Yoruba that I have to memorize.

And so that's a good three years of my life that's going to take me to memorize just that obra, and that's sort of the starter kit for babalawos, that's one of the first things we have to learn how to do. I'm gonna be learning songs and prayers and stories in Yoruba for the rest of my life. That's what I've chosen as a destiny.

The longer you do that, the more you do pick up things. And so, for example, in "Preludio," which is the first song on the record, when we do it live I add a little section where I say "Opolopo owo, opolopo oma, opolopo iré," which is "lots of money, lots of intelligence, lots of positive blessing". It's part of a prayer for some other sign in Ifá. But everyone that's Yoruba knows what this is. I was listening to an audiobook the other day, it featured a tongue-twister in Yoruba and I recognized “opolopo” in there.

How have other santeros reacted to ÌFÉ's music?

I think the reaction has been really positive. We have received really positive feedback from all over the world. Also, I had the pleasure to receive advice from Emilio Barreto, who is a singer who has been the voice for Santería ceremonies in New York since the mid-80s. I met Emilio because he walked into my studio in March, when I started working on writing material. And Emilio is in his sixties, he's an older dude, but he immediately recognized what I was doing, and understood it. He was really great because he told me at some point: "Look man, you have the ball right now, and whatever you need, I'm gonna be there for you, so you call me, if you have any question, and I'm gonna be there for you to help you work through this material, because it's my responsibility as an elder to help you." And I thought that was very powerful. And I did call him, I was hours on the phone with him working through concepts for this record, and he just gave of himself generously

I know that there are people probably that don't like what I'm doing, but I really haven't heard that kinda pushback, although I'm sure it's there. I'm not everybody's cup of tea. But I think, for the most part, it's been really positive. I'm in no way putting things that I've sworn to keep secret in jeopardy, because the things that I've sworn to keep secret will go with me to my grave. I take that oath very seriously.

I also have to say that I get a lot of questions about the religion in interviews, but actually I don't think that religion is the most interesting part about the record itself. I just think that because I, myself, on a personal level, I'm soaked in it, because of the choices that I've made in life, that the music that I'm making can't help but reflect it. And what you're hearing is more of me sort of working through my life on a personal level and trying to draw parallels and make some of the things I'm thinking about and going through accessible to people on a larger level, because some of the issues are universal.

What do you think is the most interesting part of the record?

I think it's the way you're able to be in two areas at once. The nuts and bolts of what you're hearing, the rhythms, are thousands of years old. But the vowel sounds and the pronunciation is today. I'm willing to change it tomorrow. To me, if the next songs that I make don't sound like they were made with the sounds and the letters and the pronunciation of today, I will immediately change the sounds. I don't care if somebody is using the same sounds and if other people think that they're cheesy, or whatever. I just want it to speak with the sounds of today and I think it's cool to be in both places at once, that's what's interesting about it to me.

Here's an example. In "Umbo,” the rhythm comes from a song for an orisha named Olokun. You might never know that, but other people do. It might be 20 years from now, you're gonna hear "Umbo," and you've learned the song for Olokún, and you'll be like "Oh my God, this entire time," and there's tons of that all over this record.