Joy Miessi's First Solo Exhibition Is an Ode to the Lessons Our Mothers Taught Us While Braiding Our Hair

We catch up with the Congolese-British artist ahead of her debut solo show, "Do You Know Your Middle," which is heading to London's 198 Contemporary Arts and Learning.

Do You Know Your Middle? is the title of Joy Miessi's first solo exhibition at the seminal 198 Contemporary Arts and Learning in Brixton, London. Inspired from moments shared with her mother braiding and parting her hair, these latest works are Miessi's attempt to preserve memories with each piece documenting a past experience in her life.

The North London-based artist uses the full breadth of her creative arsenal via illustration, clothing and painting to compose pieces that reference the duality of everyday life in the UK and her Congolese heritage. Miessi's signature mixed-media style formed of abstract shapes, writings and intense colours juxtaposes two cultures translating moments, feelings and intimate thoughts into emotionally engaging statements is particularly resonant with those of a diasporic disposition.

We spoke with Miessi on heritage informing creativity, building an archive and the importance of physical space in documenting the Black experience.

Christian Adofo for OkayAfrica: Your new exhibition is titled, "Do You Know Your Middle?" and that phrase borrowed from your mother speaks to a sense of grounding and reaffirming your identity. How important is it to you to acknowledge the past within your work in the present?

Joy Miessi: The title, "Do You Know Your Middle?" is something that my mum always says when defining the middle parting of my hair. It's usually a question to check that I'm paying attention but has now become a question that has helps me acknowledge the past and inform my present and future decisions.

How did your journey into art begin and where did that initial encouragement to explore creatively come from?

My dad always used to draw faces when he'd be on the phone, they'd always be on scraps of paper or on the backs of envelopes. It's not something he's ever pursued but I started drawing in the same way on materials I'd find. I would eventually be given packs of printer paper as a gifts which encouraged me to draw more and more.

It was only till I left university that I felt like there [was] less pressure to create for a grade and instead feel free in what I could make, so I went back to what I enjoyed and picking up the same habits of drawing on what's around me like my father still does.

You are a black woman born in London to parents of Congolese descent. How do the nuances of both cultural experiences and the intersection of gender, sexuality and race impact upon your creativity?

Though I've grown up in London, I see how my exposure to Congolese music and fashion and food within my home has influenced my love for color and texture within my work. The experience of living in London in areas like Camden has sparked a love for posters, typography and that DIY feel. I see my work as a reflection of myself, my identity inevitably affects my experience and therefore my work as it is a self documentation, composed of memories, thoughts and feelings that make me.

"If my story is ever to be told, then I don't want to be rewritten—I want my story to be as close to the truth as possible."

This solo exhibition is inspired by moments shared with your mum parting and braiding your hair. What was it like reflecting on the relationship between you and your mum and what was your favorite story you documented visually?

When I think about what I like about having my hair done, it is the conversations that I have with my mum during the process. She is a storyteller in a way, reflecting back on memories in Kinshasa and somehow they feel relevant to me and give me direction in my life. My favorite story is from a piece that I made called Semolina Cake—the title itself is a joke that my mum makes at every birthday party. It tells the story of us at a dinner table, when a lump of semolina accidentally falls onto the floor and so she says that her 'grandma is hungry.' The semolina stays there until we finish eating. I didn't understand what she meant at the time but I learnt how this was a call from my great grandmother and ancestors for a moment of thought. The story stuck in my mind and ended up becoming this painting, Semolina Cake, which pictures a dinner table with my grandparents at every corner making a call from Congo to myself now.

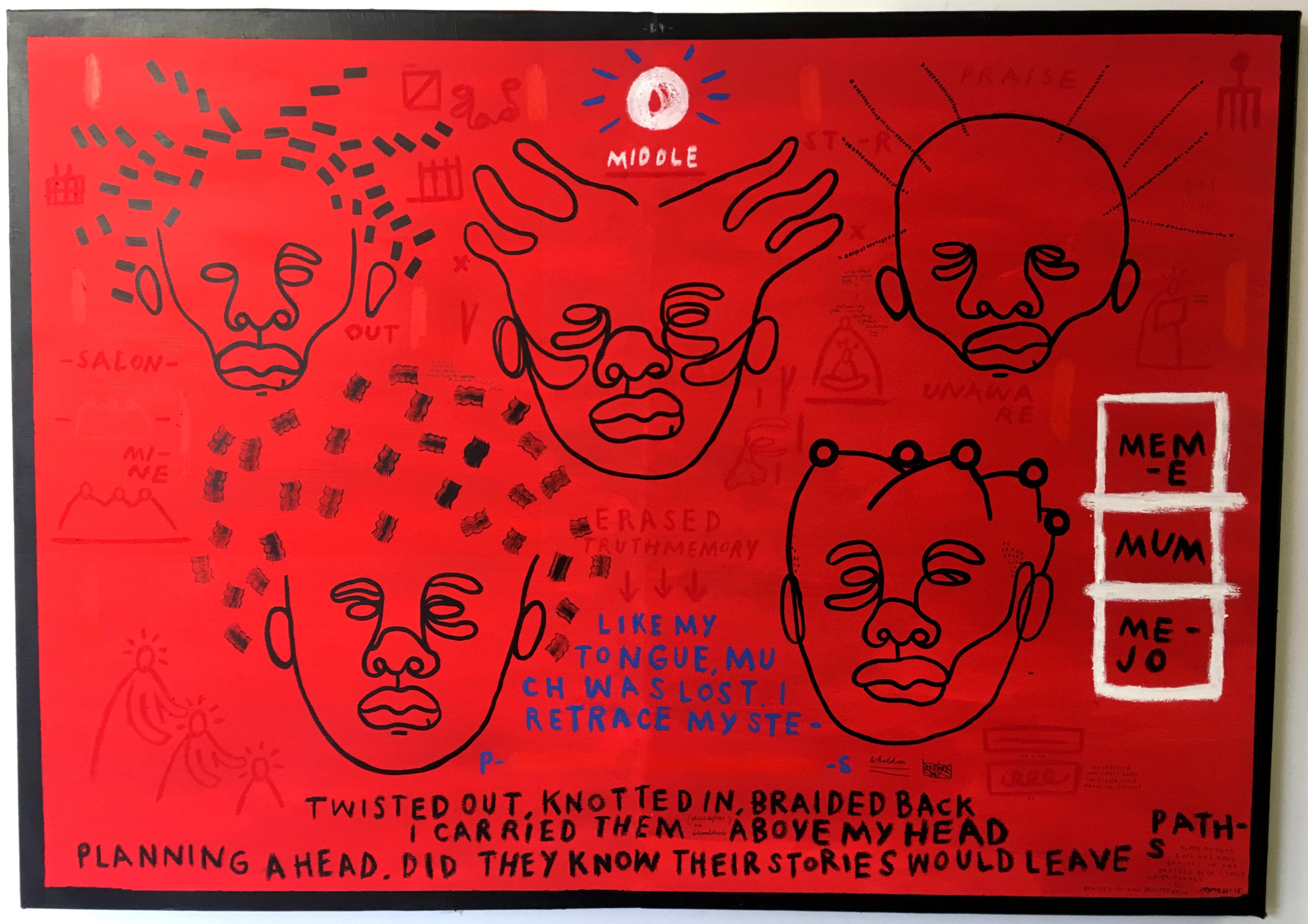

In the piece Above Your Head, you've painted a generational juxtaposition between the motherland and the African diaspora. The use of intense red as a metaphor for the bloodline. The context of your history is portrayed through faint symbolism reflecting on ancestral tales passed through generations orally whilst you're settled in the middle acknowledging and retracing the steps no matter the hairstyle. What inspired this particular painting and how do you personally maintain a connection to Congo?

Around the time I was going through a photo album and there were loads of photos with me with varying hairstyles, it brought back this deja vu feeling of the last time I was at my Grandma's house in Kintambo and I was shown photos of my mum and aunties and they all had very similar hairstyles. This piece is about how style reveals stories and paths from generations before you. Despite me growing up and being a Londoner, these styles remind myself of my heritage and family in Congo.

Animation formed part of your early creative practice and since then you've used other mediums such as illustration, ceramics and clothing to showcase your signature style. Does this collaborative stance continually unlock new ideas and what has been your most enjoyable one thus far?

I enjoy experimenting and learning new skills and techniques through collaboration with friends. It's what keeps this exciting for me. My favorite unexpected medium has actually been clothing. It's taken my art from being a static piece on a wall, to being part of someone's wardrobe and movement. It's something that I would like to create more of.

You document your process a great deal through stop motion videos and being unafraid to cross out captions on canvases. Are you mindful of building an archive and the subsequent legacy that will follow in years to come?

I never quite valued the importance of archiving until I came across the work of Zora Neale Hurston. I remembered reading a quote where she said, "If you are silent about your pain, they'll kill you and say you enjoyed it," which has stuck with me since university. My parents often retell the story of their parents, uncles and aunties but there's so much about them that is left out. If my story is ever to be told, then I don't want to be rewritten—I want my story to be as close to the truth as possible. Which is why I try to keep everything, scan it, or capture videos of the mistakes, the growth and the process. This is my visual diary.

As part of the forthcoming exhibition, your mum has also kindly provided a playlist of songs she'd play whilst doing your hair. What is it about music and the lived experiences of the songs that you feel subconsciously?

These songs have always been playing in the background bring back so many memories of my childhood. At home we'd have this old blue radio and every Sunday, my mum would put in her cd's and could be heard singing along to Mbilia Bel or Tshala Muana.

When we had a car, on our way to visit family in London and also in Kinshasa, we'd listen to a lot of the songs on the playlist. I struggled to understand what a lot of the songs were about but I enjoyed listening to them simply because my mum did, she would sing along with joy and we'd sing the last words that we could capture. If home was a sound, this playlist would be it. I wanted to include this in the exhibition as it completes the memory of what my 'middle' means to me.

Artistic expression and cultural production amongst African communities has been as a powerful tool to challenge social hierarchy based on race, the patriarchy that uses gender equality as a buzzword and the aesthetics of blackness being appropriated and resold. As a black artist holding a debut solo exhibition, why is it important to tell your narrative unapologetically in your own space?

I'm grateful that 198 Contemporary Arts & Learning has given me the space to tell my story. Historically 198 have always been a site providing a space for the black community and black artists without censorship. Their programming has always shown a diversity of artists all year round, unlike many institutions who do so only for the buzz. It's important that we collectively support spaces like 198 as they tell our stories, unfiltered and with truth when other institutions won't.

Joy Miessi's 'Do You Know Your Middle?' solo exhibition runs from July 9 July to July 27 at 198 Contemporary Arts and Learning. Check out their website here and be sure to listen to Miessi's accompanying Spotify playlist above.