How Algeria's Freedom Fighters Founded a Football Team and Created a Nation

As Algeria faces off against Honduras today at Rio 2016, we look back at the teams origins in the Algerian independence struggle from France.

In 1958, two months before the start of the World Cup to be held in Sweden, the Front de Libération Nationale (FLN), an Algerian independence movement, created the Équipe FLN, a de facto national team for Algeria, which was then still under French rule and thus barred from having a national team. Its players consisted largely of French-born Algerians, some of whom renounced their chance to play in a World Cup. But for them, playing for a free Algeria was more important.

Since then, football has been intrinsically linked with national identity and independence from colonial power in Algeria. This year, Algeria is one of three African teams to compete in the Men’s Football tournament at the Olympics in Rio de Janeiro. Two years ago, when the Algerian National Football team went to Brazil to participate in its fourth World Cup, it featured eight players (out of a roster of 23) who had been born in France and had played for youth French national teams.

What’s more, that FLN team from the 1950s featured two players—Mustapha Zitouni and Rachid Mekhloufi—who were slated to play for France in Sweden, as well as other eight players who played for French clubs, including Saïd Brahimi and Abdelaziz Ben Tifour, who had played for the French National Team.

Algerians had been fighting an independence war since 1954, but the FLN felt they needed more international support, so they created the team as a way to promote their cause, as well as an idea of Algerian nationalism, separate from the identity the French were trying to impose on them.

The team was the brainchild of Mohamed Boumezrag, who played in the French league and was the French Football Federation’s regional director for Algeria. Boumezrag convinced Ahmed Ben Bella, a former footballer in the French league himself, a leader of the FLN, and eventually the first president of Algeria, to create the team. Boumezrag then was tasked to secretly scout willing French-Algerian players and asked them to join the breakaway national team.

Even though the French Football Federation quickly managed to get FIFA to declare the Équipe FLN illegal, thus banning its member teams from playing against them, the Algerians still managed to embark on a world tour that lasted four years. They mostly played junior and military teams, but also managed to book some games with full, senior national teams, especially against other northern African nations and countries from the communist block.

Zitouni and Mekhloufi had to forgo their chance to play a World Cup, and all of the players had to resign from their respective clubs. But, for them, an independent Algeria was more important than their careers. Zitouni, for example, remarked: “I have many friends in France, but this issue is bigger than us. What would you do if your country is at war and you are called for it?”

The team has often been credited by Algerian historians and political figures as a huge advancement of the independence cause. In 2008, Algeria celebrated the 50th anniversary of the creation of the team, with various ceremonies and TV specials. Then Algerian president, Abdelaziz Bouteflika, said about the FLN players: “They wrote one of the most beautiful pages of Algerian history, of the anti-colonialist struggle, and of sport in general.”

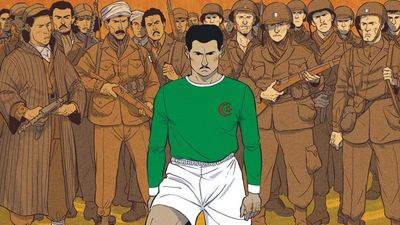

This story was most recently told in “Un maillot pour l’Algerie” (“A Shirt for Algeria”), a new graphic novel by Javi Rey, Bertrand Galic et Kris published in France. But the story does not end there.

Algeria gained its independence on July 5, 1962, and the Algerian National Team then joined FIFA on January 1, 1964. Even though many of the players form the FLN team returned for the Algerian team, the “Fennec Foxes” struggled during their first years. Algeria only managed to qualify for the African Cup of Nations in 1968, and to the World Cup in 1982.

However, Algeria won the African Cup of Nations it hosted in 1990—its first international title—and after that, the future looked bright for Algerian football. Unfortunately, a civil war broke out in December, 1991, taking the lives of at least 100,000 Algerians and ruining the careers of many young footballers. Algeria, understandably, tanked in the 1992 African Cup, but also found themselves disqualified or with early exits in the following continental tournaments. The Algerian Federation was left with a huge problem for rebuilding its team: where to find new talent?

The obvious answer was to look at France, where many French-Algerians could be convinced to play for the national team of their heritage. The French league, in addition, was more organized than the Algerian championship, and offered more tools and resources for their players to develop. Any talent injection from France, thus, would also be accompanied by an influx of technical and tactical skill.

Another problem remained, however. Under FIFA rules, a player could not change allegiance to a national team if he had already played for a national youth team. This made it harder for the Algerian Federation to scout talent, as big prospects were called up by France while still young.

So, in 2003, the president of the Algerian Federation, Mohamed Raouraoua, petitioned FIFA to have this ruled changed. FIFA’s Executive Committee agreed to one concession: players could change national allegiance as long as they had not played for the senior team, and were under 21 years old. Algeria immediately took advantage of the rule change and recruited two French-Algerian players—Anthar Yahia and Samir Beloufa—for the 2004 African Cup, where the team reached the quarterfinals.

The Algerian team made progress, but it was still not enough. Many French-Algerian players were over 21, and so were not eligible to play for Algeria. Raouraoua again petitioned FIFA for a rule change in 2009. The Executive Committee then agreed to allow any player to change national allegiance, regardless of age, as long as he had not played for a senior team.

Once again, Algeria took immediate advantage of the rule change, as three quarters of their players for the 2010 World Cup had been born and raised in France. Since, he Algerian team improved massively and the French-born players have become a staple of the team. As Algerian journalist Maher Mezahi puts it: “The French-based Algerian diaspora was meant to be an extra source of players, but it has now become Les Fennecs’ very fuel, and now many consider them the best side in Africa.”

Algeria has acquired a reputation as a team for players that are good, but not good enough for France, and it has made a lot of progress in infrastructure for its Algeria-based players. But at the Olympics, we will once again witness French-born players present on the team.

Haris Belkebla and Rachid Aït-Atmane are two players raised in France who are under the age limit (the Olympic Teams are only allowed to bring three players over 23) and that were called for the Algerian Olympic Team. Bekelba, who was born in La Courneuve, plays for Tours in Ligue 2, and Aït-Atmane, born in Bobigny, plays for Spanish side Sporting Gijón.

Algeria will debut against Honduras on August 4, then they will face Argentina and Portugal. But when the Algerian Olympic Team takes the field in Rio, we will once again be witnessing a country’s national history and football history playing right in front of our eyes.