Music In Exile: Malian Group Songhoy Blues On Their Major Label Debut

Okayafrica speaks with Malian rock band Songhoy Blues about their Atlantic Records debut album 'Music In Exile.'

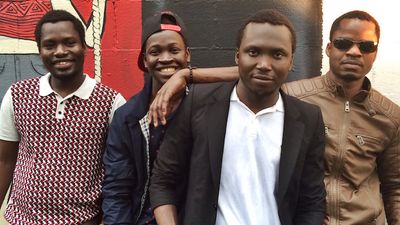

Songhoy Blues after their final SXSW showcase at Empire Control Room in Austin, Texas (Photo: Alyssa Klein for Okayafrica)

Malian four-piece Songhoy Blues got their first break when they cold-called Africa Expressproducer Marc-Antoine Moreau while he was in Bamako, which led to them recording with Yeah Yeah Yeah‘s guitarist Nick Zinner for the Maison de Jeunes album. The group's debut full-length Music In Exile, produced by Zinner and Moreau, blends contemporary elements of rock and hip-hop with the Malian guitar riffs popularized by the likes of Ali Farka Touré. The album's name speaks to the band's displacement from their home of Gao due to the growing unrest of early 2012, a story which is prominently featured in the documentary film They Will Have To Kill Us First: Malian Music In Exile.

The release of Songhoy Blues' debut full-length has made news not only because of the band's background and their alluring compositions (including lead single "Al Hassidi Terei") but also because of its label home: Atlantic Records. As Billboard points out, Songhoy Blues are the first African act the major label has signed since 1972 and, since their signing, the imprint pushed to rush-release Music In Exile last month. Such backing marks one of the larger investments in recent time from a major American label in an African group. Below, Okayafrica contributor Rob Scher caught up with Songhoy Blues after the band made waves at their first SXSW visit.

Tombouctou, Mali. January 2012.

The military’s presence looms throughout the Festival Au Desert. Gun-toting soldiers stand atop sand dunes, overlooking hundreds of Malians — and the odd tourist — congregated in front of a large stage. Rumors of an Islamic insurgency infiltrate the otherwise peaceful annual Tuareg gathering. Amidst this tension though, is the music: hypnotic Sahel rhythms sending out vibrations to an enraptured crowd blissfully transported away from their fears. Here, in this contrasting climate of fear and joy, the transcendent power of music is made real. Several weeks later the insurgency arrives, bringing with it a strict Sharia law that robs Malians of their vital culture.

Rockwood Music Hall, New York. March 2015.

Déjà vu strikes as Songhoy Blues perform to a packed room. To watch this band is to witness the indomitable spirit that defined my experience of Festival Au Desert back in 2012. Added to the familiar sounds of their forebears though, is a new element. It is an exhilaration that has emerged from surviving the hardship that at once both plagued Mali and lead to the band’s forming. It is a bold new assertion and statement of purpose for a new era of Malian music. It is Songhoy Blues.

Rob Scher for Okayafrica: How was your trip to Austin?

Songhoy Blues: Very good, it went very well.

OKA: Did you enjoy the [They Will Have To Kill Us First] documentary?

SB: We saw the film three times! We were amazed, it was the first time seeing ourselves on the big screen. We’re very happy with the film.

OKA: Now that things have become better in the North and it’s possible to play music there. Have any of you been back there?

SB: We’ve been back to the North to see relatives, but have not gone back to play yet. We’d like to only play once we’re able to do it in a proper venue and stage.

OKA: This brings us to your song "Soubour," which you say is a song about patience. I’d like to relate this to the Festival au Desert. There's something poetic about how today we see the music of the Sahel, which traditionally always reunited at the Festival, now being spread globally. I guess there's a sense — in this idea of patience — that as always, eventually the time will come again when the Tuareg will once again congregate to make their music in the desert.

SB: It’s exactly that. "Sobour" is dedicated to the people in the North of Mali to tell them "yes, they had to face the crisis but now it’s going to get better." Everybody needs to be patient and so with this song, we are telling the people this. It’s a big wish for us to once again play in the North, it is one of our main goals.

OKA: Of course Songhoy Blues wouldn’t exist if it weren’t for what happened. It seems kind of ironic that through this attempt to suppress cultural traditions, instead it’s caused the opposite to happen, spreading the music wider than ever.

SB: All the guys were part of different music group before, but because of what happened, out of that negative side of the occupation it’s become a real positive thing. In the end, we are very happy to have found each other and be making music together.

OKA: Let’s talk a bit about your sound, which has received a lot of attention for its energy and exhilaration. There’s at once that familiar, hypnotic rhythm of the Sahel, but it carries your ‘Songhoy kick.' Added to this amazing celebration and defiance — with songs like "Desert Melodie" and "Mali" — there’s that theme of displacement?

SB: For us, out of the problems, we have been unified and with that there is a need to find positivity in an otherwise dire situation.

OKA: So, on this idea of unification, much of the music of the Tuareg people is about celebrating each nomadic group’s identity. Now with your group we have something similar with you flying the banner of the Songhai, though you don’t just represent them but also the entire land of Mali?

SB: We talk as both Songhai and as Malians. Malians are unique in the way they are able to put aside their differences and all get together. In the time of the Songhai Empire, there were many different ethnic tribes that became incorporated into the state. The way, we see ourselves as the 'Songhoy Blues' is to once again do this: unite together and bring all the different tribes in Mali together as one.

OKA: And how has that translated to the people back home in Mali?

SB: We are trying to spread this message of unification, but it is only the beginning for us. We are not that known in Mali, we have some followers coming to our shows but we’re still far from ambassadors yet. Certainly though, it is something we aim for in the future.

Rob Scher is an NY-Based South African writer and polyrhythm enthusiast. Follow him on Twitter.