Cinema Africa: Ethiopian Legend Haile Gerima On His Civil Rights Masterpiece, 'Ashes And Embers'

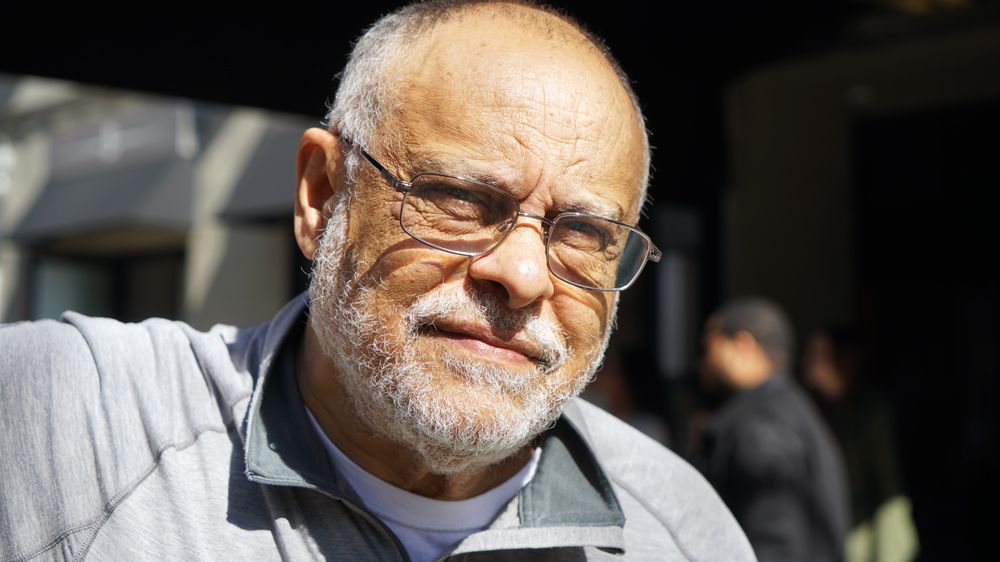

Legendary Ethiopian filmmaker Haile Gerima sits down with Okayafrica to talk the re-release of his 1982 film 'Ashes and Embers.'

In the fifth installment of Okayafrica’s Cinema Africa series, legendary Ethiopian filmmaker Haile Gerima discusses the re-release of his 1982 film, Ashes and Embers.

Two black men in America get pulled over by a cop and fear for their lives. The opening scene of the rarely-seen 1982 film Ashes and Embers feels ominously like the present day. And although the Ethiopian-born cinematic legend Haile Gerima might insist otherwise, there’s something incredibly timely about his story of an African-American Vietnam veteran returning stateside.

Although a landmark project for the now 70-year-old trailblazer of black cinema, Ashes and Embers was never actually seen in theaters. 34 years later, the film is finally getting a proper release through Ava DuVernay’s distribution company, Array. As of this month it’s available for Netflix streaming and, for the first time ever, it’s being shown in theaters across America, where a new generation is being introduced to Mr. Gerima’s uncompromising, lifelong commitment to a career in film totally outside of the injustices of the Hollywood system.

A tenured professor of film at Howard University as well as the co-founder (along with his wife, filmmaker Shirikiana Aina) of the legendary D.C. bookstore and black arts and culture space, Sankofa–named after his 1993 cinematic masterpiece–Mr. Gerima is hard at work these days editing his new documentary about the 1935 Ethiopian-Italian War. He’s also on a nationwide tour for Ashes and Embers.

We sat down with the legendary filmmaker in the lobby of his New York City hotel last week for a very special installment of our Cinema Africa series.

Can you tell us about your experience outside of Hollywood?

All I know is independent film. I went to school with Native Americans, African Americans and some folks from places that at the time were dubbed Third World countries. We knew then that the whole vocabulary in Hollywood is white supremacist. I felt there was no breaking through that. I wanted to spend time—even if it took me a long time to do a film—outside that mainstream arrangement of cinema expression.

You've talked about building alternative institutions. What institutions have you seen that are already in place?

I think Ava DuVernay and Array are trying to pick up where we failed. The last time we succeeded was when we opened Sankofa. My wife and I are both independent filmmakers who distribute our own films. I was able to make films by going to Europe and Africa. It took me years to put resources together. Sankofa, a film about slavery, didn’t get much support in the United States. American Playhouse, National Endowment, they weren’t interested. They felt it was alien. They felt it had too many African names in it. They didn't see it as an American story. They assumed the enslaved population had never had a name of their own choosing as a form of resistance.

We went to Europe—Germany specifically—Channel 4 England, WDR Arte in Germany, and we did the film. That was very innovative. It's an imperfect film [Sankofa], but we had the audacity to put together a film to shoot on location in Jamaica and in Ghana and Burkina Faso. It's unheard of. This is a story not many people are exposed to.

Your techniques were really radical at the time, like your resistance to using makeup on the actors. Can you tell us a little bit about that? What about the language of cinema in terms of how you tell your stories?

Well the best example would be jazz. If black people hadn’t insisted on the musical format of jazz, it wouldn’t have existed. When jazz popped up from underground, it was immediately met by hostility. It was called coon music among other things. But it survived. I bring that up to say the accent of jazz musicians, the thing they brought with them—their African and American experience—forged a musical vocabulary, a language.

What I’m saying is, ‘Well, what is our cinema supposed to be?’ And having come from Ethiopia, the logic of thinking in how you tell a story is not in this cookie-cutter, three-act Hollywood way. It doesn't fit well. Our accent doesn't fit well, our logic of thinking, our thought process does not fit. That I knew at a very early stage.

Then the folks I was with at UCLA, we knew we had to defend how we tell a story. We got the idea of defending our logic of telling stories. I mean, I'm more coherent now than when I was a student, but we were angrily defending something.

For me, that also goes into makeup. For example, the makeup that is smeared on Hollywood actors comes from the theater, and it also has a psychological dimension. When you question color, for example, what does green mean or red mean to Senegalese Wolof-speaking people or Amharic-speaking Ethiopian people? And so I look at traditional arts, African arts, bead women, the women who organize beads, they seem to know lighting. And why would I learn from the mainstream formula? So the psychological meaning of color itself is not coming from the same origin.

Then I followed it to the makeup, because I felt black people didn't need makeup. This I saw when I traveled in Africa. The sun creates this very red kind of skin tone. And I felt it could be achieved by just tanning folks. Even now, when I did Teza, unless it's special effects, I don't put makeup on people. We just make sure they tan well. That’s it.

What advice do you have for young filmmakers of color and young African filmmakers who are encountering a similar sort of experience that you had when you were coming of age in the 70s?

Theirs is more difficult. I'm glad I'm going to pass out of this whole complicated world. It's very difficult for them. I'm not sure they know what their accent is. The American empire, especially after the Second World War, has completely muddled the world’s accents. America has created a middle class all over that has been bred by American culture. Young people are just born into it and they think it's normal. Most of them I see in Africa just imitate television because that's what they were born into. I was born into my grandmother's fireside, so I knew the crackling fire. I knew my grandmother telling a story. And my father was a playwright, a traditional playwright at that. Mine is easier to resist than fighting the colonial aesthetics sort of mindset. It's easy for me.

For them it's complicated, because they’re born into the mess. The technology itself has expedited their colonization process. I don't think they even realize they are colonized. They feel they’re born into a normal world, but their expression doesn't have their essence. It doesn't have their mothers, their fathers, their experience. Even the music they use is straight out of television. It's not even Hollywood. Television, that's another part of the whole thing.

Generational transaction is not easy. I would say to them, first, study where you come from. Accept who you are. It's normal to think different from the mainstream colonial mode of thinking. And you don't come to cinema empty-vesseled. You come by genomics, you have many rhythms and things that are put in the vibrations of your mother's placenta.

And to learn techniques of filmmaking, they shouldn't confuse imitating the language. It's good to have an idea of the aesthetics of their story, of how they place their camera for example. They should learn that, but they shouldn’t be brainwashed at the same time. These are some of the tragic things I see. They're imitating the scriptwriting and exhausting white people's stories. The formula is exhausting it. Even in the 1960s, 40s, there was diversity. Even if it was all whites in Hollywood, there was accent diversity. Southern white folks, like Tennessee Williams's script would come in, it has its own texture and rhythm and structure and aesthetics and way of thinking. So there was diversity. Some came from Ireland, some came from Sweden, Russia, Italy.

But now it’s all converged into a formula for capitalism. The people who control the industry have simplified it and have mutually created an audience that is addicted to that formula. It's a very incestuous relationship: audience and the film industry. I'm sure a lot of individual white American filmmakers suffer a lot to fit their story and choke it into this bottle, because the audience themselves are into that conditioning.

With Sankofa, I've seen interracial people coming in seeing it and taking whatever they could out of it. It's for everybody in the end, because racism is the most divisive part. To me, the liberals in Hollywood have been driving the community with a white supremacist vocabulary that has kept people divided. It's the most divisive. No civil rights movement ever demonstrated on Hollywood.

You hit the language, you rearrange its usage, expressions. Human relationships follow. But when the dominant culture says white people are number one and everybody else is an appendage, in the way the Bible says women are ribs, it's crazy, it's not acceptable. But Hollywood continues to do that.

I saw something my kid showed me, this guy called somebody Oliver did a Hollywood take.

John Oliver...

Oh my goodness, it was so historical, so precise what he picked up. He just missed Casablanca, but it's amazing. That was a forceful intervention in this new crisis of the Academy Award. People need to target this industry if they are for a better planet, especially for American race relations. To me, Hollywood tells little black kids, little Native Americans that they don't matter, they're not history makers, they're spectators. They come as sidekicks to drive Mr. Daisy and Ms. Daisy. This arrangement is fascist to me. I don't accept it. To me all human beings should tell their story. In the way Joseph Campbell talks about the story of the world, the global story, and how similar, how healing it is. Instead of this dictatorship of white is right and white is everything.

What was your take on #OscarsSoWhite?

I have no time for them [the Oscars]. I make my films. It takes me twenty-hundred years to finish a film. The last time I saw an Academy Award was when Brando ruined their evening dinner and had his Academy Award [received by] an Indian woman.

Even now, it's not only black folks. It's a serious issue for all little kids that grow up in America. The role-playing idea, that is the most tragic part of it. How kids are affected by it. I myself, I was in Ethiopia, far away, but we were playing cowboy and Indian in Ethiopia, and it felt natural for us to go to the mountain and play. Then I came to America and I saw Native American issues. We accepted the savage paradigm and none of the kids wanted to play the Indians. We'd wear a hat and start having a shootout. And where is this coming from? It’s the John Wayne, Glen Ford movies that we saw when we were young people.

If you want to democratize society, you need to fight to change the culture, the expressions of an institution like movies and theaters. Latin Americans called [the role-playing] the new hydrogen bomb when I was going to school. It's very true. It does change the world by just single bombs. Single movies can make women of a certain country change their hair, their nose, their lips. It's tragic.

Why is it important to you that Ashes and Embers is getting re-released?

My wife and I both prefer to make movies. When we did Sankofa we never thought we'd do distribution. But we also felt if nobody's doing it that cares about the stories we're making, we’d do it. So for [Ava DuVernay] to come and propose to me [Array’s distribution], it's like, "take it. Let me see what you can do." That's what I said to her [Ava DuVernay]. I don't expect her to not face issues with distribution, but she is very intelligent, has a good business mind, and I think she's heading in the right direction.

Why is it an important film to screen today?

I don't think it's an important film. In fact it's a very imperfect film. I think it's really her [Ava DuVernay’s] technique of distribution, how she's doing it in the way she’s showing it. For me, it's a film that was torpedoed by racism. I think it should've been showed. An audience should've judged its merit. I think it's a very interesting film, especially about the African American Vietnam experience and its implication in their family structure.

In Los Angeles and in Washington, D.C. when it showed, it was packed. It was a generation I have no access to. She has amazing access to a very interesting population. I think her endorsement is going to do well for my work. Like the younger people who might have dismissed the past, maybe they’ll say, "Oh, let's go look at the other filmmakers that he went to school with too.” So it might help give them perspective. However imperfect those of us who were at UCLA were, I think we are leaving films that are fooling around with important things in the audiovisual organization of stories. Even when we failed, the experiment could be picked up and done better by a generation coming in the future.

Especially for storytellers—I'm waiting for the days where African Americans can just control from green-lighting to the end, a story that they feel is relevant, and then share it with the world. I don't think it should be controversially standard by the arrangement where a white person dictates the making or not making of a film about a grandmother that is from an African American specific community. If they leverage that kind of economic power, it would be good.

In our case, we did a lot of the business outside. We never succeeded in America. We didn't even succeed to make banks embrace our idea. We've never succeeded to leverage bank loans for cash flows. Most African American film companies, if they have no cash flow, they can never circumvent the problem.

How do you think your film speaks to the modern-day black soldier returning from combat overseas?

Yesterday at Amherst they were talking about how relevant it is, because fundamental things are still in place. Some thought we made it now because of the police issue for example. Although I don't go for current events at all in my films. I was much more interested in working against the white American’s idea of orphaning black people. Because when you obstruct them from their genealogy, they're orphans, and when they’re orphans, they're open to abuse by police, by self-violence, by every kind of toxic...

What I do is I put humans in context, even in Ashes and Embers. It's one of the films I did where the young man under police gun comes from somewhere, genealogically. He's a human. For me that's very important, because that's what was destroyed in my view by mainstream literature and the idea of white supremacy in film narrative. Black people are orphans. You see that many times. For example, Morgan Freeman is never a human being with a human interest. He's always a buffer to something. In a Clint Eastwood movie about boxing, there's a white woman who wants to be a boxer. Clint Eastwood is training her, and the black guy lives in his place. This is bad news for cinema.

It reminds me of Casablanca. When I went to film school, white students and black students, we used to fight about it, because we felt the black man in Casablanca has no purpose to live except to provide music to Bogart and Ingrid Bergman. Which is fine, but what does he do? Does he have a sex life? Does he have human emotions, etcetera?

When you see them reoccurring again it’s offensive. Young people are made to think they are nobody, they are just an appendage. For me, this kind of organizational arrangement of stories is at the expense of the future children of America, because both white kids and black kids are being disfigured by the idea that black people have no home to go or human relationship. For me, this context itself is important. I don't think black filmmakers can afford to not put context within the story. They have to always wonder how multidimensional their characters are or not. If they’re not, you know, black people are also capable of recreating stereotype. The multidimensional characters are very, very important.

Do you feel like your film speaks to the Black Lives Matter movement?

[Pauses] No. I would like to speak to them, and I would like to say, "It's good, you guys are fantastic, but then again, don't stop there. What is the next step?" Otherwise it's like, "I Am A Man," which was in the Civil Rights movement. Well, you're a man, then what's the next step? So revolutionaries, like Malcolm X and Cabral, would challenge them and say, "Okay, fantastic, I bless you. Let me hug you, because so many young people are not as involved as you are, but then what's the second step?" Otherwise you're going to be a musical note of resistance.

If they use Black Lives Matter, okay, I will scrutinize that and re-position the next level of the slogan. Decolonizing the mind is key. Fanon will be very important. Any slogan we have, we have to use the past knowledge to reassess and forge and calibrate the struggle, but not make it one. If you stranded it, shrink-wrap it now, it would be a business. It would be like Black Lives Matter combs, Black Lives Matter hairdos, Black Lives Matter stockings, underwear. It would be commodified, because capitalism's capacity to commodify dissent is what has kept it this long.

That's what I would say to them. I want to hug them, but then after that I want to say, "Okay, what's the next thing?"

If you were to make Ashes and Embers in 2016, what would change about it?

Nothing. That was like a note. I'm very emotional about my films. All my films were honest expressions of my own rage. My film expressions prevent me from shooting. They are the bullets I shot. They are my rockets, because I don't like destroying people. I don't like killing people. My films are my smart bombs. They're shot into orbit and there's no change. I have a sequential film for it called Chicken Bone Express. But as it is, it's a package. Like it or not, I ain't changing anything.

'Ashes and Embers' is now available to watch on Netflix via Array. Look for the film to screen in a city near you and head here for a full list of dates for Array's 'Ashes and Embers' screening tour.

- Women Tell the Story of Ethiopia’s Red Terror In This New Documentary from Tamara Dawit - OkayAfrica ›

- Anbessa: A Beautiful Story of A Child's Escape Into Imagination As A Coping Mechanism For Displacement - OkayAfrica ›

- Haile Gerima On the Need For African Filmmakers to Reflect On a Continent That 'Lost Its Mind' - OkayAfrica ›