Why Brazilians are Embracing Afrofuturism

The afrocentric philosophy of imagining a black future is finding a rich following among young Afro-Brazilians

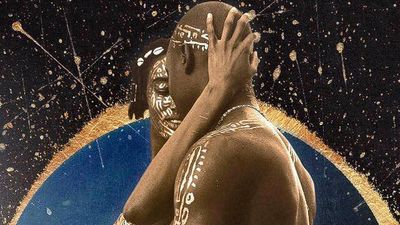

The film poster for the "A Jornada" film would be striking in any country. A dark-skinned man and woman, naked but covered only in gold geometric shapes, lovingly embrace each other. In Brazil, a country where advertisements never show black couples or even dark-skinned black people, the film poster is an affirmation of blackness for Afro-Brazilians—something very daring and even dangerous in the country.

"It's rare to see black people as protagonists in Brazilian film," said Jonathan Ferr, a jazz musician who produced "A Jornada," a three-part short film that uses Afrofuturism to promote black love. "I wanted to create a new paradigm for black people in film. I created a totally new world. The Kingdom of Tundee is a fictitious name that represents the African content. We created an entirely new society in which black people are able to create the life that they want."

Ferr is part of a new generation of Afro-Brazilians who are reclaiming and affirming their blackness through the lens of Afrofuturism. For them, Afrofuturism means changing the future in order to change a past that was forced upon them. In reality, that past consists of Afro-Brazilians suffering from 400 years of slavery, racism, and classism. Although Brazil is more than 50 percent black, European history, culture, and standards of beauty are idolized over their African and Afro-Brazilian counterparts. Even today, television does not reflect Brazil's racial diversity. So many young Afro-Brazilians grow up seeing few positive representations of themselves outside of the home.

"For these youth, and for black people who are into media and culture, Afrofuturism has become an alternative to the Eurofuturism that is imposed upon us daily," said Fabio Kabral, author of the book, "O Caçador Cibernético Da Rua 13 (The Cybernetic Street Collector of Street 13)." "It's so much more than simple representation. Afrofuturism has surged to become a real possibility to create a future in which we exist and are revered and to reconfigure a past where we were traditionally neglected."

Thus, Afro-Brazilians are using Afrofuturism to imagine a future more empowered than what even they would call a second-class reality.

According to Ytasha Womack, author of the book, "Afro-Futurism, the World of Black Sci-Fi and Fantasy Culture," people can live their entire lives embracing the concepts of Afrofuturism without knowing the term. "I was always Afrofuturistic without knowing the term existed," she wrote in her book.

Many of the Afro-Brazilians who embrace Afrofuturism today didn't even know it existed three years ago. Kênia Freitas was one of the first Afro-Brazilians to embrace the term and promote the philosophy. In 2015 she produced and curated a film festival in São Paulo called "Mostra Afrofuturismo: Cinema e Música em uma Diáspora Intergaláctica" (AfroFuturism Showing: Cinema and Music in an Intergalactic Diaspora). All of the films hailed from the African diaspora and presented the stories about black people's past, present, and future in a fantasy and alternative way.

"The audience didn't know what was Afrofuturismo," Freitas said, who had just discovered the philosophy a few years prior. "They wanted to get to know it and be closer to it. "

She also noticed that the festival attracted large amounts of black people, an uncommon sight in Brazil's large cultural centers where the festival occurred. Since then the word Afrofuturism has become much more common in Brazil and people continue to stumble across the film festival online, often reaching out to Freitas for more info.

I was always Afrofuturistic without knowing the term existed

According to Freitas, Afro-Brazilian short-film directors are also producing Afrofuturistic films that critically examine Brazilian society. "Chico" (2016) by the Carvalho brothers imagines a Brazil in 2029 in which every black child is expected to become a criminal, and therefore enters prison at a young age. "Personal Vivator" (2014) by Sabrina Fidalgo, imagined an alien visiting Rio de Janeiro to study the inequality between races and classes. In "Rhapsody for a Black Man" (2015), Gabriel Martins uses the mythology of Afro-Brazilian religion to show the political and racial relationships in an urban Brazilian city.

For author Fabio Kabral, the Afro-Brazilian religion of Candomblé has had the biggest impact on his expression of Afrofuturism.

"It's just been more than a year since I was initiated as a son of Oxóssi following all the sacred rites," Kabral said. "This totally changed my perspective and my understanding of ancestry."

Kabral's "O Caçador Cibernético Da Rua 13" is a science fiction story inspired by Yoruba mythology. It's a story about an imagined society in which the top 10 percent, the super powerful, make the rest of society submit to them. The central character, João Arolê, is part of the 90 percent but has the opportunity to become a superhero when there are a series of murders. By using Afrofuturism to narrate the exciting trajectory of João Arolê, Fábio Kabral teaches Brazilians about black culture, gods, and ancestry.

Despite Afrofuturism's hold on young Afro-Brazilians, the country's most famous artist of the philosophy is Elza Soares, an 80-year old woman who first became famous by singing samba. In 2015 she released "A Mulher do Fim do Mundo" (Woman at the end of the World), an earthy electric-pop album full of songs that talk about violence, sexism, racial hierarchies and even homophobia. The way she speaks honestly about racism and homophobia has attracted her legends of young Afro-Brazilian fans. Her concerts, where she sings perched upon a six-foot throne, are a rite of passage for them.

"Maybe Elza can speak about this better than me, but Elza is always updating and singing the demands and victories of [Afro-Brazilians]," said Ellen Oléria, a singer who won Brazil's "The Voice" competition in 2012." "She acts among the forces of inheritance and promise, ancestry and hostility.

Like Kênia Freitas, Oléria's discovery of Afrofuturism was an academic process that eventually helped her to realize that she was an Afrofuturist. She says it started when her wife, Polianna Martins, took university class in 2012 called the "African Diaspora in the Americas," and shared with her the bibliography and syllabus. The class' professor explained that the miscegenation of black people in the Americas had essentially left them to become cyborgs, enslaved and dehumanized but still possessing human power. Oléria's own research into cyborgs, led to her discovery of Afrofuturism.

"Afrofuturism is a discourse, a language, an esthetic, an identity and political network, even a place that updates the legacies of the African Diaspora (especially of the African peoples in the Americas and the Caribbean," said Oléria when asked what Afrofuturism meant to her. "It's a connection between the technology of production and the reproduction of knowledge in the contemporary world."

She identified with Afrofuturism so much that she named her 2016 album, "Afrofuturista." Oléria is known for an acoustic and organic sound but she says that with this album she wanted to modernize that sound.

Young Afrobrazilians like Morena Mariah are hoping that Afrofuturism becomes a movement that touches all of the country's Afro-Brazilians. Mariah, 26, is the founder of INOVA CoLab, a marketing and audiovisual company that creates campaigns using the philosophy and aesthetic of Afrofuturism. But she thinks Afrofuturism is even more powerful than this.

"I believe there is a future where we are not living and thinking under eurocentric philosophy," she said.

- 11 Afro-Brazilian Artists You Should Listen to - OkayAfrica ›

- Spotlight: Kevo Abbra's 'Kibera Ghost Rider' Is Afrofuturism Personified - OkayAfrica ›

- 9 Songs That Showcase the Greatness of Elza Soares - OkayAfrica ›

- Boddhi Satva & Nelson Freitas' 'Goofy' Will Transport You to the Dance Floor - OkayAfrica ›

- 7 Must-See Afrofuturist Films - Okayplayer ›