Interview: How Climate Change is Bringing Deadly Cyclones to East Africa

Cyclones Idai and Kenneth are a taste of what's to come, warns Sudanese climate expert Abubakr Salih Babiker.

As the remnants of Cyclone Kenneth continue to hammer northern Mozambique with rain, people in the region are wondering if this is the new normal. And they're right to. Kenneth is the first hurricane-strength storm to hit the Mozambican province of Cabo Delgado since record-keeping began and has already impacted hundreds of thousands of people fleeing damage from wind and flooding. But the true scope of its impact won't be known for a long while, as the rain is scheduled to fall through the week.

Kenneth comes on the heels of Cyclone Idai which hit central Mozambique just six weeks earlier, killing more than 600 people and devastating Beira—a city of half a million. To many, the scale of these storms is a clear indication of a global slide toward climate catastrophe—a situation where centuries of industrial-scale polluting by the global north comes back as devastation for people living near the equator.

But anything to do with climate science is still highly politicized and not widely understood on a popular level. To Sudanese meteorologist Abubakr Salih Babiker, the pattern is clear—the waters of the western Indian Ocean have been warming at a rate faster than any other region of the tropical oceans and a sharp increase in violent storms like Idai and Kenneth is the result. He sums it up this way: "What used to be rare, is not rare anymore."

Salih Babiker works for the IGAD Climate Prediction and Application Center, providing climate forecasts to the governments of East Africa. We reached him in Nairobi, Kenya.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

I watched your video on Twitter and it gives some good context. So, what is unique about Cyclones Idai and Kenneth?

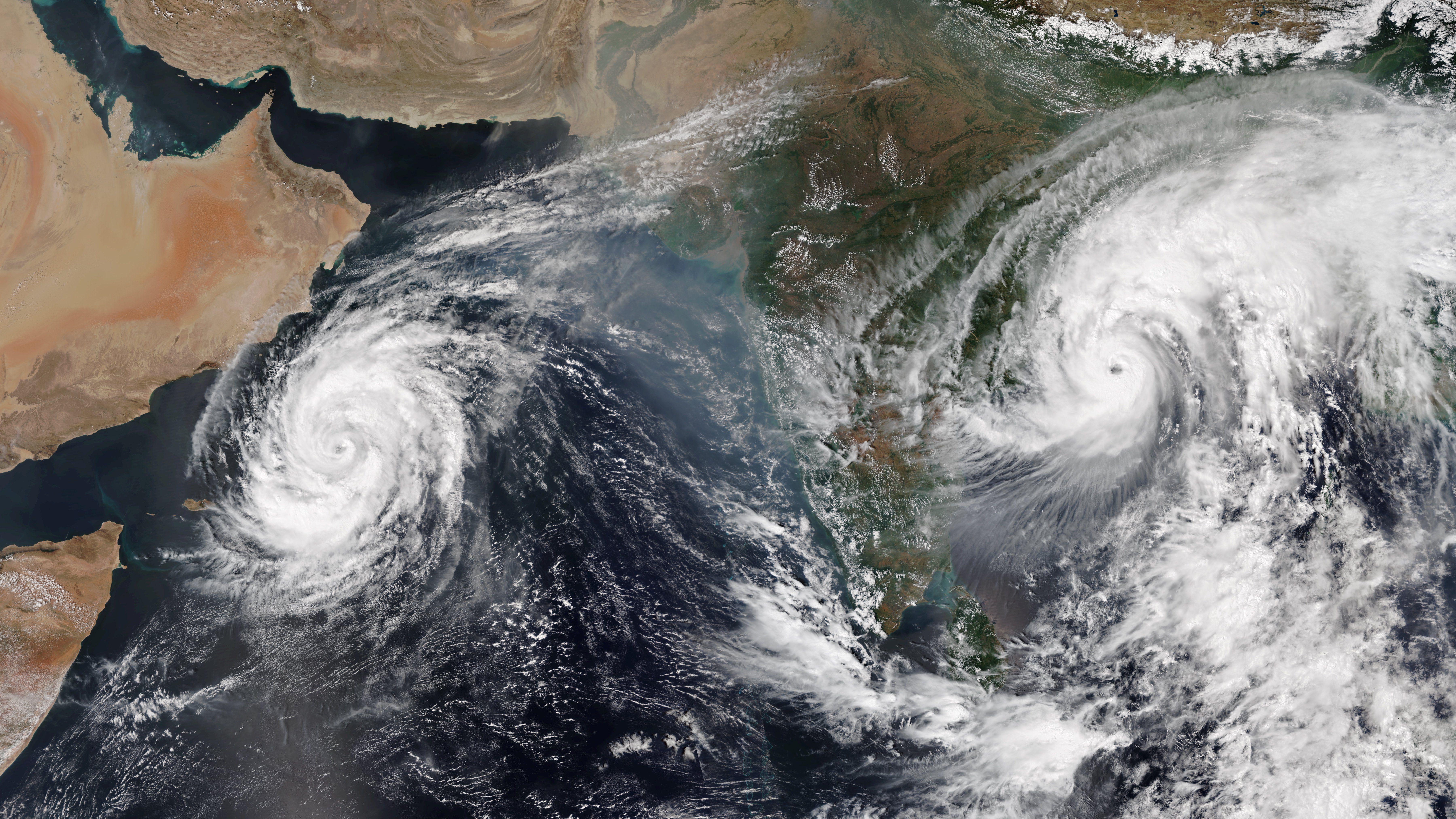

In the video, I start with the cyclone that hit Somalia last year—Sagar. It's the strongest on record for Somalia. And the same year there was another rare case in the northern Indian Ocean where two cyclones developed simultaneously. I think it only happened one time before. In the southern part of the Indian Ocean it's historically very rare to be hit by a tropical cyclone, because when they develop around that area of eastern Africa, they tend to curve southward, avoiding Mozambique. And now it's been only five weeks between Idai and Kenneth. Idai was classified as the strongest to have hit Mozambique and now this one is even stronger. And it hit a region of Mozambique that isn't used to being hit by tropical cyclones at all. This is something new.

So, there's a pattern here where they're becoming more frequent, more intense and we believe that has something to do with climate change, because the basic ingredients for tropical cyclones are the warming of the ocean. The warmer the ocean, the stronger the tropical cyclone, and the warming of the ocean, of course, is a result of the warming of the whole global climate system.

Right. So historically scientists who study climate change would be reluctant to say this one storm or this one busy hurricane season, for example, is caused by climate change but now that seems to be changing. Why is that?

So, they are careful in the way they give their statements because for example, a tropical cyclone is a weather event and you cannot blame a weather event on the whole climate because the climate is more long term. But the point here is that it is not one tropical cyclone. Like you cannot say Idai, by itself, is the result of climate change. But with Idai, you can now say that this is the strongest tropical cyclone on record to hit Mozambique and five weeks after that we have another tropical cyclone that is even stronger than that. Then you have another one in Somalia that is the strongest in the record. And you have another case in which two tropical cyclones developed in a region where they never develop in this simultaneous way. So you have a series of events that are rare in their nature and are outliers from the record. And since the basic ingredient is warming, I think there's enough evidence to suggest that climate change is responsible for this kind of weather pattern.

And, and so what would you tell people in power to do in regards to climate change and the rise in devastating storms?

Our regional governments have to update and improve on their policy around disaster. For example, there's the Sendai framework for disaster risk reduction. But they have to go forward and actually implement the measures suggested there so they can build more resilient infrastructure and advise and train their communities. It is more cost effective. If your infrastructure—public roads and buildings and those sorts of things—are resilient then you are very likely to survive. Instead of waiting until the disaster hits, you have to be prepared earlier.

Climate change is a global issue and we in Africa are less polluting. The solutions, then, are in the more developed countries: they have to cut their emissions on carbon and all the other greenhouse gases so we can control the warming at the bounding level—a survivable level.

So, in terms of mitigation it really has to come from western countries. But preparing for the impact of climate change has to come from African countries?

Yeah, exactly.

What can the East African region expect in the next 10 years or so in terms of a changing climate?

It is a bit hard to say that without a proper analysis. But if you read the IPCC report they warn against a business as usual scenario. So if we continue burning more fossil fuels and putting more greenhouses in the atmosphere, it will increase the warming. And I really believe that a warmer climate is more susceptible to severe weather events. It will increase this tendency of severe weather events.

If you look at tropical cyclones, in a way they are a mechanism for the system to distribute energy around itself. It's releasing the tension from itself in this violent way. So, with more warming on a system that is rotating, and it is moist—moisture plays a bigger role in releasing latent heat over the ocean—when it is warm over the ocean, the air starts to rise up and then when it goes up it will condense because the upper layers of the atmosphere are a bit colder, so when it condenses it will release huge amounts of heat and that fuels the system. A warmer ocean or a warmer atmosphere will cause more severe weather events.

Besides cyclones, what is the impact of climate change on East Africa?

The region depends on rainfall as a main source or for agriculture. So, for agriculture and for livestock, they also depend on rain-fed pasture. And hydrological power is also a major component of the energy system in the region. So there are several sectors of the economy that are, you could say, climate dependent. It will become even harder to predict the season.

Plus, there are changes in the seasonal cycle. I have seen results from one of my colleagues that shows that the shortening of the growing season is a general trend in our region—a shortening of the time period where you have enough rainfall to grow the crops. So yeah, these are the complications for the economy and the livelihood of the region.

What is the goal of your work?

Our main goal is to encourage people—the government, the farmers, hydrologists, disaster risk practitioners—that they get this idea of planning around climate, because climate here is variable by definition. It is not like Europe and the middle latitudes where the seasons are well defined and the variabilities are less pronounced. Here in East Africa, there is huge variability from year to year, from month to month. So the only mitigation that has to happen is that we plan around the climate.

Aaron Leaf is OkayAfrica's Managing Editor. Follow him on social media: @aaronleaf.

- Cyclone Kenneth Could Be the Second Damaging Storm To Hit ... ›

- How East African Musicians Are Making Money Today - OkayAfrica ›

- The 6 Best East African Songs of the Month (May) - OkayAfrica ›

- The Best East African Songs of the Month (February) - OkayAfrica ›

- The 7 Best East African Songs of the Month (July) - OkayAfrica ›

- The 6 Best East African Songs of the Month (August) - OkayAfrica ›

- The 6 Best East African Songs of the Month (January) - OkayAfrica ›

- A Climate Conversation In Africa, Without Africans - OkayAfrica ›

- The Best East African Songs of 2022 - OkayAfrica ›

- Longest-lasting Storm Freddy Kills 190+ in Southern Africa - OkayAfrica ›

- Malawi’s President Says Half the Country Damaged by Cyclone Freddy - OkayAfrica ›

- The 6 Best East African Songs of the Month (March) - OkayAfrica ›

- The 7 Best East African Songs of the Month - Okayplayer ›

- Spotlight: 'Weaving Generations' Confronts Environmental Destruction in Côte d'Ivoire - Okayplayer ›

- Kenya Declares Surprise National Tree Planting Day Holiday - Okayplayer ›

- Unprecedented Flooding Ravages Somalia, Displacing Hundreds of Thousands - Okayplayer ›

- Activists Want Shell to Take Responsibility for Damage to Nigerian Communities Amid Sale Announcement - Okayplayer ›

- South African Weather Service Issues Alerts as Severe Conditions Hit Parts of the Country - Okayplayer ›

- Photos of destruction after Cyclone Kenneth ravages Mozambique ... ›

- Photos: Cyclone Kenneth Tears The Roofs Off In Mozambique ... ›

- Death Toll From Tropical Cyclone Kenneth Jumps to 38 in ... ›

- Mozambique: Cyclone Kenneth lashes southeast Africa, killing 38 ... ›

- Mozambique: Cyclone Kenneth aftermath in pictures - BBC News ›

- Cyclone Kenneth Pounds Mozambique, Killing at Least 5 - The New ... ›