Da Capo’s Journey to Become an Afro-House Torchbearer

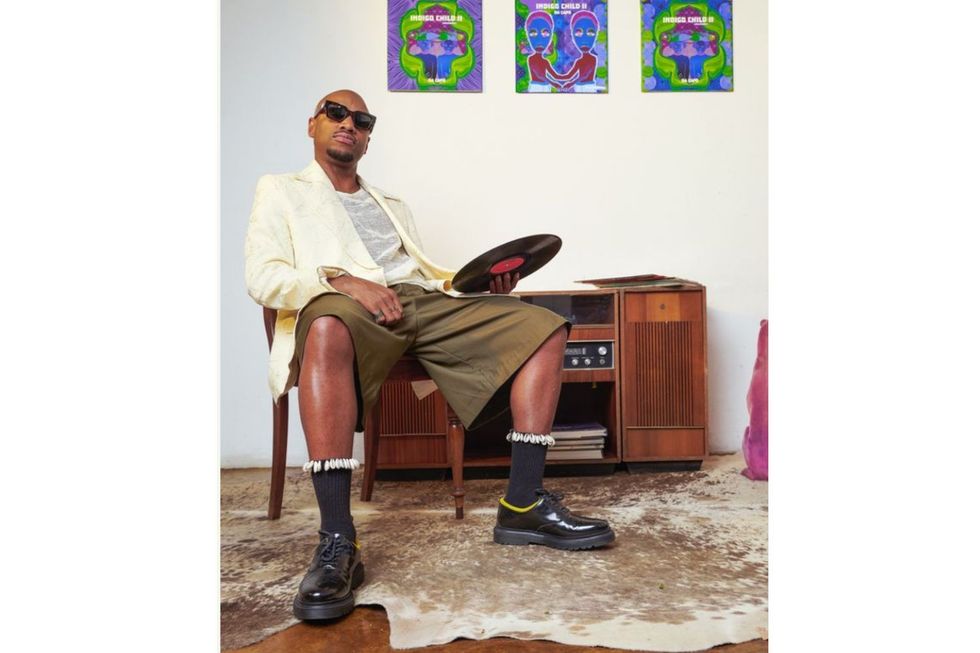

With his new album, 'Indigo Child II: Love and Frequency,' the South African producer asserts himself as one of the most original voices in electronic music.

Da Capo’s ‘Indigo Child II: Love and Frequency’ arrives eight years after the first one.

When it comes to aura, few possess it like Da Capo. The DJ and producer, who was raised in Seshego, Limpopo Province, and shaped by a deeply musical upbringing – his mother a jazz dancer and his grandfather a trumpet player – now sits firmly among the upper echelons of global music culture. A key architect of the Afro sonics movement, his influence extends deeply across genres such as Afro-house, Afro-tech, and 3-Step.

Da Capo is rarely home nowadays. He's become a globetrotting sonic pioneer whose impact on the scene is undeniable, with countless up-and-coming producers citing him as a foundational figure. During an hour-long conversation, Da Capo spoke with OkayAfrica about creating a follow-up to his acclaimed 2017 release, Indigo Child, which featured powerhouses such as Wanda Baloyi, Jackie Queens and Berita, how he balances the demands of international travel and performance with the need to keep an ear on the ground (he has a team that curates a monthly folder full of new music), and how his journey from bedroom hip-hop producer to budding upstart entirely changed upon being discovered by Nick Holder — who subsequently released his first public offering in 2009.

Then came the compilation album, featuring Punk Mbedzi mixed by DJ Swizz, the 2016 Ibiza residency under the guidance of Black Coffee, and numerous remixes for artists such as Tresor, Nduduzo Makhathini, Phuzekhemisi, Zaki Ibrahim, Louie Vega, and more. He even explored techno territory in 2023's unafraid Bakone.

Indigo Child II: Love and Frequency, his fifth studio album in as many years, is an outstanding body of work that contains all the traces of his journey so far, along with some outlandish and mind-boggling sound design that sounds like the future knocking on our doors.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Why did you decide to release Indigo Child II now?

Everything is God's timing. You can plan something, and then it doesn't happen, which means it wasn't the right time. The album was bound to be released at this very moment. I had the project for more than two years, trying to spread it out and find which songs people would fall for. The plan was to drop it in 2021.

What do you admire the most about the person you've become since the original Indigo Child album in 2017?

Being a leader, being at the forefront of the culture, being someone that people look up to, being a grootman (elder) of the game. I've done so much for the culture, and now the culture is giving back to me. I'm talking about fellow producers, people who look up to me. I travel all over the world, and people tell me I'm a pioneer. They tell me that they've drawn inspiration from me and that they wouldn't be doing this without me.

What are your thoughts on the global reception of the Afro-house movement? Is there an imbalance between people who make it and those who consume it? As the originators of the sound, are you still in control of the narrative of where Afro-house goes?

This is the ongoing war between the European Afro-house and our Afro-house at the current moment. A majority of people feel like Afro-house is starting to become commercialised, losing its authenticity. However, to someone who has been in the space for such a long time, I feel that Afro-house is currently growing in a positive direction. Take a look at how many Afro-house producers from South Africa are expanding their reach globally. Back in 2011, 2012, and 2013, you would have never found any South Africans making moves all over the world. It was super limited. Currently, everyone can have a slice of pie. As long as you're pushing the sound into the right spaces, we'll appreciate you and show you love.

When do you decide when a song is done?

It never ends. After giving Indigo Child II to DSPs, I went back to a couple of songs. I didn't like how they sounded. So I told that team to take the uploaded songs down. We fixed the songs and sent them back. Even when I listen to it today, there'll be something that sticks out.

When did you start working on the album's first song, "Funa Wena?"

Our studio session with Ndoni for that song was so funny. She wrote the song, then asked everyone to go out before she was about to record. That was a really fascinating moment for me. She's a true creative. She recorded the song, and I went back home and listened to it. The vocals were spiritual, so I needed to create something that would complement them, as the original track had a different beat.

How did the song with MaWhoo and Soul Star, "Phakade Lami," come about?

The song started as a remix of Tracy Chapman's "Fast Car." If you listen to the instrumentation, it's written for her vocals. I was just challenging myself. I posted it on SoundCloud and YouTube, and people fell in love with it. Soul Star heard it on YouTube, then he removed the vocals, kept the beat, wrote and recorded a new song, and sent it to me. I was blown away, and I wanted it to be the lead single. It was a good song, but I felt that we needed another person on it. The first person that came to mind was MaWhoo. Without her, that song was not gonna come out.

How did the Miči session go, and what was your favourite session from this album?

That was the one, the one with Miči. It was my favourite because she is the first person to ever write and record a song on the very same day. We had a different beat; she jumped in the studio, wrote the song, and recorded it herself. I went home after that and created a new melody to accommodate her.

Da Capo's first release was with Nick Holder in 2009

Photo by JR Ecko

How did growing up in the township of Seshego influence your love for music, beyond the influence of your immediate family?

It was the lifestyle, the way guys lived. There was a time when there was a culture of bo-majaivane (dancers). They used to do items (dance routines) back in those times, and it was so cool. I also wanted to be like them, but I'm unfortunately a terrible dancer, so I couldn't fit in that space. They would dance to house music, I guess that's where the influence comes from. I was more fascinated by the production. This was between 2004 and 2008. There was a point where I had to choose between my studies and pursuing my music career, and I opted to go for music.

When does DJing come into the mix?

I'm a very shy person. I just wanted to be the guy in the background. I just wanted to make music. I feel more comfortable in the studio than I do on stage performing for people. Fans wanted to see the guy behind the music production; they demanded my presence. I then decided to showcase myself. I looked at it this way: I never viewed myself as a DJ at the time; I just saw myself as an artist.

The sound called 'Sgubhu' (bass-heavy music) has evolved so much over the years. What was it referred to when you were starting?

We had ancestral music, the likes of Boddhi Satva and Osunlade, which paved the way for artists like Culoe De Song, Mushroom Boyz, and Infinite Boys. That's when the movement started, where we now had this new African flavour that we brought within that Ancestral Soul. From there, it gave birth to what we refer to today as Afro-tech.

When did you start working with vocalists?

My first release was with Nick Holder's DNH Records. That was just instrumentals. I started merging my music with vocals on my second project in 2010. The first person I recorded a vocal track with that was officially released was Lyrik Shoxen. In 2009, music was not as accessible as it is today. It was an era when people were transitioning from CDs to the internet. We had DSPs such as Traxsource. Beatport wasn't even popular in South Africa at the time. Here, we had a DSP called Afrodesia MP3. That's where hardcore Afro music originated. It was accessible to people who had credit cards at the time, but it was generally difficult for our fans. Most of the music was accessible via file-sharing services like Bluetooth and so on.

Both Nick Holder and Black Coffee co-signed you at crucial points in your career. What were those moments like?

Both of them were life-changers, but the one for which I will forever be grateful was when Nick Holder discovered my music. I remember that it was difficult to get your music out. You had to have distribution, and you needed to have a label. At that time, we had limited information. I approached so many guys, and a lot of people rejected it. Nick was the first guy who said, "Yo, I love what you do, and I think I'm gonna release your music." With Black Coffee signing [to Soulistic Records], he broadened the brand in the sense that he was for the culture. Look at everyone that he has worked with, guys like Culoe De Song, Zake Bantwini, Shimza — they were all under Soulistic at that time, and it was like an empire. Everyone wanted to be there. It had so much power. Black Coffee elevated the culture and has done a lot individually as a person — many of us drew so much inspiration from him, and how he's been moving.

- 10 Classic South African House Songs You Need to Hear ›

- Black Coffee Brings South African Magic to Drake's New Album, 'Honestly, Nevermind' ›

- Niniola Is the Nigerian Queen of Afro-House ›

- Listen to Simmy’s New Album ‘Tugela Fairy (Made of Stars)’ ›

- Simmy Drops New Single 'Emakhaya' Ahead of Highly-Anticipated Sophomore Album ›

- African Songs You Need to Hear This Week ›